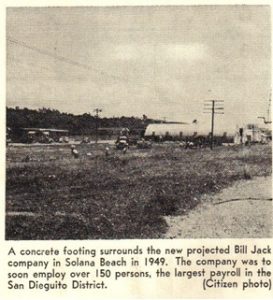

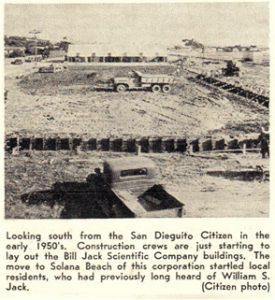

After World War II, the Solana Beach community began to grow. The Chamber of Commerce was formed. A sanitation district and a fire district were created. For a 10-year period between 1950 and 1960, the community underwent tremendous growth. The Bill Jack plant on South Cedros (1949) brought industry into the area and private contractors built a number of homes. [source: Solana Beach – Forty Years of Progress, 1922-1962, The San Diego Citizen, April 1962.]

William S. Jack came out of retirement in the late 1940s to establish the Bill Jack Scientific Instrument Company. While he became well known for his forward thinking and innovative business practices, his legacy also includes the row of Quonset huts that now house businesses in the Cedros Design District. These lightweight, semi-circular, prefabricated structures, used primarily by the Army, were attached together along Cedros Avenue. “He put the Quonset huts up because he needed a place for people to work quickly,” said Nancy Gottfredson of the Solana Beach Civic & Historical Society. The repetitive roofline of gentle curves quickly became a landmark in Solana Beach and, later, many of the Bill Jack huts have been reconfigured into shops and restaurants.

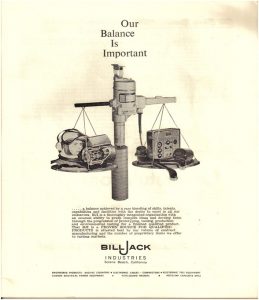

Jack’s company, which employed about 600 people, built, among other things, reconnaissance photographic equipment, motors, tachometers and police helmets. In the early 1950s, it began making helmets for fliers who were just beginning to break the sound barrier. “Indy drivers wore them, too,” Gottfredson said.

Jack was ahead of his time in his concern for his workers. He called them “associates” and treated them like partners in his business, sharing profits with them and helping them buy homes, Gottfredson said. Much was learned about Jack and his business quite by chance. When Dave Hodges, former owner of the Belly Up Tavern, was remodeling his Quonset hut, he found a box of news clippings and other memorabilia about Jack and his company, which he turned over to the historical society. From that box, Gottfredson and other historians learned that Jack’s story began in Cleveland, Ohio, where he was born in 1888. According to a yellowed, undated clipping from the Maple Heights Press in Ohio, at age 15, Jack quit school to learn the die-sinking trade. In May 1917, Jack started his first manufacturing business with $2,000. Soon after, he earned a government contract. He had four months to finish the project and earned a bonus for every day the project was completed under deadline.

Jack finished the project in 45 days and made a huge profit. He used it to begin other manufacturing enterprises, which he built up and eventually sold. One of the sales changed his life. It was agreed he would stay on as the manager after the sale, but after a disagreement with the new owners, he was fired from a business he had founded. This motivated him to organize another business that would put the needs of the employee first. Sandra Bigsby’s father, Andrew Lev, worked at that first innovative plant in Cleveland. She remembered her father talking about his work there. Because of government contracts, the workers were needed 10 hours a day, six days a week, to make aerial camera control systems. “It was wartime,” said Bigsby, 62, of Del Mar. But Jack made it worth their while, she said. At 4 p.m. there would be a break when food was provided along with massages. There was a steam room and gym on site. Jack also paid for life and health insurance for his associates. Vacations were paid and not just the time, but the travel, food and lodging at resorts.

Jack eventually turned the business over to his nephew, Clayton Jack, who ran it until the government contracts were completed.

Learn more about the company here.

[source: Patty McCormac, The San Diego Union-Tribune, April 18, 2004.]

Boo-Boo had been looking forward to the Historical Society’s Halloween party all month. He had never been to one before, and was excited to dress up in his best white sheet.

Boo-Boo had been looking forward to the Historical Society’s Halloween party all month. He had never been to one before, and was excited to dress up in his best white sheet. Jackie o’Lantern was feeling excited as she made her way to the community center by the sea. It was the earliest Halloween party of the season, and Jackie loved nothing more than dressing up and celebrating with her friends.

Jackie o’Lantern was feeling excited as she made her way to the community center by the sea. It was the earliest Halloween party of the season, and Jackie loved nothing more than dressing up and celebrating with her friends. The Jinx attended the earliest Halloween party of the season, at a community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon and the days might finally start to get chilly. The Jinx was excited to attend his first Halloween party, but he was also nervous. What would he wear? He had no idea what costumes humans wore. He decided to go as himself and flew to the party in a cloud of dark smoke.

The Jinx attended the earliest Halloween party of the season, at a community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon and the days might finally start to get chilly. The Jinx was excited to attend his first Halloween party, but he was also nervous. What would he wear? He had no idea what costumes humans wore. He decided to go as himself and flew to the party in a cloud of dark smoke. Obscuro was getting excited for the upcoming Halloween party. It would be his first one of the season, and he was looking forward to dressing up in his favorite costume. He had white latex skin that made his face look like a mask, so he always stuck out in a crowd. But that was exactly why he loved going to Halloween parties- he loved the opportunity to show off his unique look.

Obscuro was getting excited for the upcoming Halloween party. It would be his first one of the season, and he was looking forward to dressing up in his favorite costume. He had white latex skin that made his face look like a mask, so he always stuck out in a crowd. But that was exactly why he loved going to Halloween parties- he loved the opportunity to show off his unique look. Lucius Morte had never been to a Halloween party before. He had always been too busy tormenting the damned in the 4th level of hell to bother with earthly celebrations. But this year, he was feeling particularly restless and decided to venture out into the world of mortals. He found a community center by the sea that was hosting a Halloween party and decided to attend.

Lucius Morte had never been to a Halloween party before. He had always been too busy tormenting the damned in the 4th level of hell to bother with earthly celebrations. But this year, he was feeling particularly restless and decided to venture out into the world of mortals. He found a community center by the sea that was hosting a Halloween party and decided to attend. Vespera was so excited to go to the Halloween party. It was at a community center by the sea, and it would be her first party in a long time! She had been practicing her mime and charade skills for weeks, and she was determined to show everyone how good she was.

Vespera was so excited to go to the Halloween party. It was at a community center by the sea, and it would be her first party in a long time! She had been practicing her mime and charade skills for weeks, and she was determined to show everyone how good she was. Gourdy Bane was very excited to attend the earliest Halloween party of the season. It was being held at a community center by the sea, and he loved the sound of waves crashing against the shore. When he arrived, he saw that the party was already in full swing. There were pumpkins everywhere, and people were dressed in costumes. Gourdy Bane saw a couple of gourds wearing pirate costumes, and he couldn’t help but laugh. He loved Halloween parties, and he was having a great time dancing to the music and eating candy.

Gourdy Bane was very excited to attend the earliest Halloween party of the season. It was being held at a community center by the sea, and he loved the sound of waves crashing against the shore. When he arrived, he saw that the party was already in full swing. There were pumpkins everywhere, and people were dressed in costumes. Gourdy Bane saw a couple of gourds wearing pirate costumes, and he couldn’t help but laugh. He loved Halloween parties, and he was having a great time dancing to the music and eating candy. Morrigana was very excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and the days were finally starting to get chilly. Morrigana had been working on her Halloween outfit all year long, and she was looking forward to showing it off.

Morrigana was very excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and the days were finally starting to get chilly. Morrigana had been working on her Halloween outfit all year long, and she was looking forward to showing it off. William Wisp had been looking forward to the community center’s Halloween party all month long. It was going to be two days before the full moon, and he loved the smell of fall in the air (cinnamon and pumpkin spice). His Halloween costume was all ready to go, and he was excited to show it off to all of his friends. This year, he was dressed as a pumpkin. His little orange boots matched his little pumpkin body perfectly.

William Wisp had been looking forward to the community center’s Halloween party all month long. It was going to be two days before the full moon, and he loved the smell of fall in the air (cinnamon and pumpkin spice). His Halloween costume was all ready to go, and he was excited to show it off to all of his friends. This year, he was dressed as a pumpkin. His little orange boots matched his little pumpkin body perfectly. Mr. Creepers was all dressed up and ready to go to the community center by the sea for the earliest Halloween party of the season. It had been a long time since he’d been out and about, but he was feeling young at heart and ready to have some fun. He loved the black 1940s coat that he had found at a thrift store and felt confident that he would be the most stylish person at the party.

Mr. Creepers was all dressed up and ready to go to the community center by the sea for the earliest Halloween party of the season. It had been a long time since he’d been out and about, but he was feeling young at heart and ready to have some fun. He loved the black 1940s coat that he had found at a thrift store and felt confident that he would be the most stylish person at the party. The Frankster had always loved Halloween. He loved the costumes, the candy, and most of all, the parties. This year, he was especially excited for the party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and he could feel a tiny bit of a cool autumn breeze in the air.

The Frankster had always loved Halloween. He loved the costumes, the candy, and most of all, the parties. This year, he was especially excited for the party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and he could feel a tiny bit of a cool autumn breeze in the air. Wooblydook was really excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. He had never been to one before, and he was looking forward to kale pulling and making neep lanterns. The party was two days before the full moon, and Wooblydook was hoping it would start to get chilly soon. He loved being out in the cold and feeling his bat-like ears flap in the wind.

Wooblydook was really excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. He had never been to one before, and he was looking forward to kale pulling and making neep lanterns. The party was two days before the full moon, and Wooblydook was hoping it would start to get chilly soon. He loved being out in the cold and feeling his bat-like ears flap in the wind. As the sun began to set, the community center by the sea came to life. Lights flickered on, announcing that the earliest Halloween party of the season was about to start. A golden sun slowly rose in the sky, growing brighter and brighter as it got closer to the horizon. As it reached its peak, people whispered: this sun only came out at night. It was the Midnight Sun.

As the sun began to set, the community center by the sea came to life. Lights flickered on, announcing that the earliest Halloween party of the season was about to start. A golden sun slowly rose in the sky, growing brighter and brighter as it got closer to the horizon. As it reached its peak, people whispered: this sun only came out at night. It was the Midnight Sun.