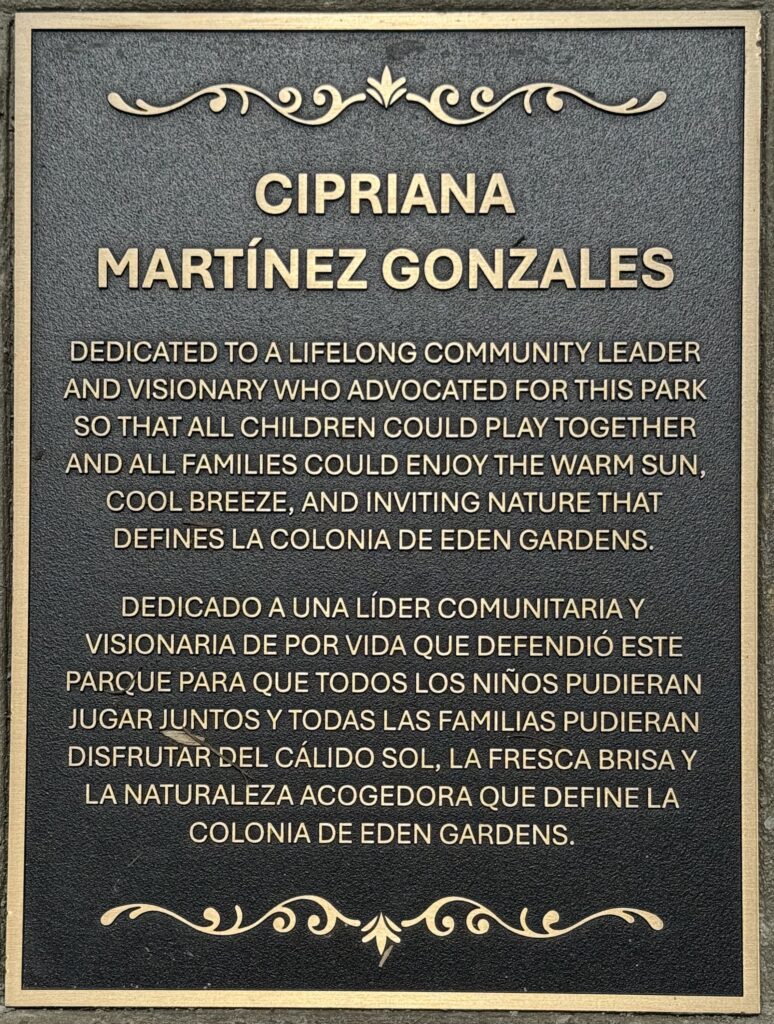

La Colonia Park Playground dedicated to “la madrina” Cipriana Martinez Gonzalez

Gonzalez family members joined Solana Beach Council-members to celebrate “Cipri’s Playground” during their family reunion in July 2025.

Cipriana Gonzalez (1906 to 1999) spent most of her life in La Colonia, where she was a tireless advocate for the community. She married Salvador Gonzalez in 1926 and the two raised five children together.

In the 1930s, Cipriana fought to end segregated Americanization schools where Mexican-American youth were forced to “assimilate” into American culture and punished for speaking Spanish. Two decades later, her efforts influenced the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme Court desegregation case, according to her grandson, Prof. Daniel Ramirez.

She was a life-long supporter of St. Leo’s Church, advocating for its construction after World War II and leading the fight against efforts by the Catholic Diocese of San Diego to close the church during the 1960s. She famously took that fight to Rome by writing to the Vatican and was victorious in preserving St. Leo’s as a Mission. Cipriana organized sewing circles to make its altar linens.

She also led the Solana Beach Mothers Club and supported the Boys & Girls Club. She believed, family members said, that “all children should play together.”

High-tech is Helping to Survey a Historic Cemetery

A long-sought investigation is underway at the historic cemetery tucked behind St. Therese of Carmel Catholic church in Carmel Valley. High-tech ground-penetrating radar (GPR) technology has been deployed to help identify unmarked graves so they can be honored and protected. The latest survey took place on November 8, 2025 and was shared in this video reported by KPBS San Diego.

The project has been a decades-long dream of caretakers Michael Beltran of the La Colonia Community Foundation (LCCF) and Armand Olvera, a church parishioner and member of the Knights of Columbus. The pair and their organizations lead twice- yearly maintenance programs at the cemetery. The land is owned by the Catholic Diocese of San Diego, but brush-clearing, grave-stone cleaning and general care of the hallowed grounds is an entirely volunteer operation.

Armand literally stumbled across the cemetery about 20 years ago, just out of curiosity about what was under the four- to six-foot brush behind his church. “I came down the hill and was walking through the thick brush and I tripped and fell over one of the gravesites.” That sparked his effort in 2006 to enlist the Knights of Columbus in their semi-annual clean-ups. Michael’s small army of LCCF volunteers joined with annual November and April clean-ups nine years later after he and his father had a similar discovery. “I looked over the hill and saw just the top of a headstone. The growth was two- to three-feet high. . .My dad stayed down there and I went to my truck to get tools so we could start cleaning. When I came down, my dad stopped me and said ‘Mijo, I found my. . .great grandmother.’ “

She was one of many former La Colonia residents buried there. Michael’s great aunts and uncles are, also. “Years back, when people died, this is were we came to bury them,” recalled Michael’s father, Joe Beltran, who now is 96.

Armand scoured church and diocese records to research the history of the cemetery. It wasn’t easy. Over the years, the burial ground had grazed by cattle, scorched by brush fires that destroyed wooden markers, and vandalized. In the Death Register Book kept at St. James Catholic Church in Del Mar, he found that the cemetery has 83 recorded burials — the last recorded in 1980 — in two sections: Catholics to the west; Protestants to the east. So far, volunteers have found 57 gravesites, based on visible evidence. To honor the unknown, they erected white crosses.

But Michael and Armand have been pining to scan the depths of the graveyard for years. They contacted archeology and anthropology professors at the University of San Diego (USD) and the University of California at San Diego (UCSD). They also invited Ken Kramer of KPBS’s “About San Diego” to visit the site and tell its history. From USD, Dr. Marni LeFleur reached out to James Daniels, Jr. of Michael Baker International, who in turn contacted Michael to say he was interested in helping — at no charge.

Michael Baker is global architecture and engineering firm with more than 85 offices across the company and 4,500 employees — including Senior Archeologist James “Jimmy” Daniels, based in Carlsbad. MBI’s cultural resource management team includes archaeologists, architectural historians and historians who provide regulatory compliance services for developers and government agencies to protect sensitive historic and archaeological resources. They conduct surveys and evaluations of both archaeological and built-environment resources. GPR is one of many tools they use in their work.

Drones are another. To develop a precise, multi-dimensional survey of the cemetery, Jimmy was joined on his second visit by fellow archeologist and drone pilot Nick Doose, who works for ASM Affiliates, another cultural resource management firm founded San Diego in 1977 and with projects around the country.

At each marked grave, during the duo’s December 6 visit, Nick placed a small device to capture its precise geographic position by satellite and then launched his drone for a complete aerial survey of the cemetery.

Meanwhile, Jimmy drove his GPR device, in precise “transects” of roughly 50 centimeters each. The device — made by Swiss-based Screening Eagle — looks like a lawnmower with a tablet-sized screen. On the screen, Jimmy looked for underground “anomalies” — signals that there’s something beneath the surface that’s different than the surrounding soil. At each anomaly, he staked a flag. Another colleague took photos of each marked gravestone.

For Jimmy, the pro-bono GPR service offered a way to help MBI market its archeological survey capabilities — the crew’s work has been covered by The Coast News (December 27 edition) and KPBS. But mostly, he said, “I enjoy doing GPR surveys and being able to use technology to solve problems that matter to people…I love what I do and want to share that in a way that’s meaningful to others.”

Volunteers Tend Historic Cemetery for Solana Beach First Families

Michael Beltran vividly remembers when he and his father found the first grave in what they had heard was an early cemetery for Solana Beach founders. The year was 2015. The pair had been given permission to explore a weedy ravine on the south side of St. Therese of Carmel Catholic Church in Carmel Valley, between Highway 56 and the church.

“I looked over the hill and saw just the top of a headstone. The growth was two to three feet high. . . My dad stayed down here and I went to my truck to get tools so we could start cleaning. When I came down, my dad stops me and says ‘Mijo, I found my grandmother. My great grandmother.’ ”

“He had been stationed in Japan when she passed away and was just under the assumption they took her back to Arizona. He had no idea that she was here this whole time. . . I could see it in his eyes, how happy he was to find her.”

After finding that grave, father and son began hunting for others, eventually clearing headstones — some intact, many damaged — bearing the names of many of the families who initially settled into La Colonia de Eden Gardens and who worked in the valley for the Sisters of Mercy or on the nearby ranches of Rancho Santa Fe.

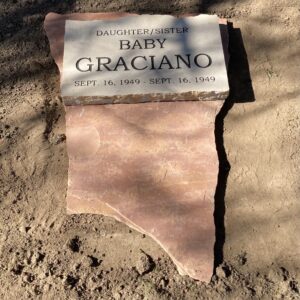

It quickly became apparent that clean-ups would require additional hands. Twice yearly since then, Michael and his sister have organized cleanups of the cemetery, which otherwise is only mowed yearly by the Knights of Columbus. They whack weeds, clean stones and leave artificial flowers. Eventually, they uncovered another set of gravestones — Catholics and Protestants, were buried on opposite sides of the 1.5-acre site.

They have also found unmarked graves and erected white crosses to honor them. Michael hopes to work with researchers who can use underground sensing technology to find more graves.

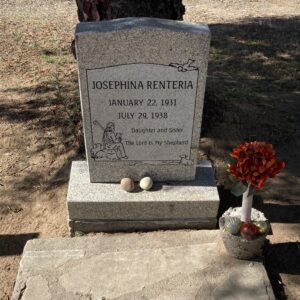

In June, 1995, Terry Renteria, then Mayor of Solana Beach, wrote to the San Diego Catholic Diocese in an effort to have the cemetery declared a State of California Historical site. At the time, Carmel Valley was booming with the construction of the housing and commercial buildings that now occupy the area, and construction of Highway 56 was on the horizon. Terry Renteria’s sister, Josephina Renteria is buried there.

In June, 1995, Terry Renteria, then Mayor of Solana Beach, wrote to the San Diego Catholic Diocese in an effort to have the cemetery declared a State of California Historical site. At the time, Carmel Valley was booming with the construction of the housing and commercial buildings that now occupy the area, and construction of Highway 56 was on the horizon. Terry Renteria’s sister, Josephina Renteria is buried there.

Diocese Death Register records say the cemetery has 83 recorded burials, but the true number probably exceeds 100 because many turn-of-the-century burials went unrecorded. The last recorded burial was in 1980. “No one seems to know where the non-Catholic burials were recorded,” according to St. Therese website history, cited here in italics.

The cemetery was part of a 1,000-acre plot owned by the Sisters of Mercy, who ran St. Joseph’s Hospital and Sanatorium, now known as Mercy Hospital in San Diego. The Sisters of Mercy arrived in San Diego from San Francisco in 1890 and . . . acquired the land from the McGonigle family, who were Irish settlers and the first Anglos to settle in the valley. They homesteaded 2,040 acres . . . in the late 1800s.

When the McGonigles couldn’t pay their $4,000 mortgage, they offered the Sisters of Mercy 1,000 acres to clear the bill. After they died, McGonigle family members were buried in the cemetery, but the wooden crosses that marked their graves were destroyed and no record of their burial site remains.

In the early 1900s, the sisters built a three-story Victorian house on the land, then called Mount Carmel Ranch, adjacent to the cemetery. During World War I, the ranch was used as a home for neglected children, funded through donations to the sisters. The nuns also raised vegetables, primarily beans, and dairy cattle on 300 acres of the ranch, and the money this brought in was used to build a surgical wing at the San Diego Hospital. In 1919, a group of investors thought there might be oil on the property and the sisters agreed to allow drilling, including on the cemetery plot, for which they would receive 12.5 percent of the oil. However, the oil venture never materialized and the sisters continued their farming.

The nuns were given permission to sell the land in 1935 for a minimum of $100,000. Three years later, the state of California indicated it was interested in buying the land for a state prison, but political considerations interfered and the land was passed over for one in Chino. Eventually, the sisters were able to sell all but 10.69 acres of the ranch.

According to records kept at the Catholic Diocese of San Diego, Mother M. Michael Cummings donated the cemetery and an adjacent 10–acre plot in 1894 to Most Reverend Bishop George Montgomery of Los Angeles. In 1937, Most Reverend Bishop Buddy, obtained a transfer of the deed to that property from the Los Angeles Diocese. This land is controlled by the Catholic Diocese of San Diego and maintained by St. William of York Church, now renamed St. Therese of Carmel.

The first recorded burial was Juana Jauriqui on Valentine’s Day 1919, who died of “old age,” according to church records. Since then, there have been no more than seven burials in any one-year and no burials in 17 of the years between 1919 and 1980. The earliest burial date still legible on the gravestones in the Protestant section of the cemetery . . . is for Caroline Nieman, 1839-1899. Her husband, Martin Nieman, 1833-1908, lies nearby under a matching marker.

Also in the Protestant section, there is a concrete marker with a metal plate. The inscription, no longer legible, included the names of Miles and Virginia Standish, who died in 1956 and 1957. There is a legend that these were descendants of the Miles Standish, Captain of the Colony of New Plymouth in 1621. The Standish family came from Montana and are believed to have had a farm south of Del Mar, west of Interstate 5.

A Lost Cemetery is Rediscovered

Lively Centennial Celebration Launched La Colonia’s Second Century

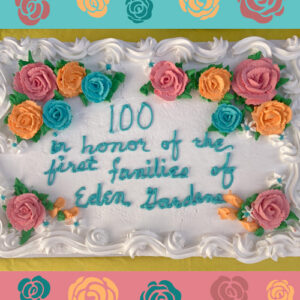

In September, 2021, the Historical Society and La Colonia Community Foundation hosted a (one-year delayed, due to the Covid 19 pandemic) grand fiesta to celebrate the founding of Solana Beach’s first neighborhood in 1920.

Among the 160 guests were Mayor Lesa Heebner, Deputy Mayor Kristi Becker, Councilmember Kelly Harless, and former Councilmembers Judy Hegenauer, Joe Kellejian, Peter Zahn and Marion Dodson, who was on the first City Council upon incorporation of Solana Beach in 1986. Virginia Garland, SBC&HS president emeritus, and her husband Bob also attended.

A huge birthday cake was supplied by Priscilla Rojo, president of La Colonia Community Foundation, and cookies were provided by nearby Santa Fe Christian School. Tony’s Jacal catered, serving up the 75-year-old establishment’s signature turkey tacos and enchiladas.

Fourth generation resident Lisa Montes, Society historian and Heritage Museum curator — and the lead organizer of the event — remembered that, 30-years ago, Connie Alto encouraged Elba Montes to start Ballet Folklorico Jalisciense in La Colonia. Her charming dancers entertained during the evening. Mariachi Estado de Oro provided music for the dancers and serenaded guests.

Descendants of many of the first families to settle in La Colonia shared their memories of growing up in the neighborhood and playing along Stevens Creek in what is now La Colonia Park. Many provided family photos, which were presented in a looping slideshow throughout the evening.

View the slideshow here.

“My great grandfather, Francisco Guiterrez … purchased a lot of the lots here. And he was a great builder, skilled in a lot of building methods. He helped build a lot of the buildings that are still standing here today, including his own home,” remembered attorney Joe Villasenor.

“He was a leader in bringing water to our community, as well.” Francisco had nine children “and those children and their heirs still live here today,” he continued. “We are really proud to continue the tradition and build on the legacy that was established by our forefathers.”

View Joe’s testimonial here.

Christine Hernandez Aleman recalled the fight the community launched to preserve the very community center and park where the fiesta was held. “We took many, many, many hours fighting for this with the supervisors in San Diego. It was earmarked for condos, both sides. As kids, we all came here . . . To play baseball. The guys would play football. It was a great place to live and be raised and raise our own. It’s a sacred place for me . . .”

Arthur “Ono” Sentano paid tribute to first-generation resident Robert “Chuckles” Hernandez, whose memories are chronicled in Early Solana Beach by Jim Nelson. Chuckles was instrumental in developing the Veterans’ Memorial Wall and courtyard at La Colonia Community Center. Arthur’s daughter Sarah was a 2020 recipient of the Society’s college scholarships.

Teresa Rincon, who with husband Ray now manages Tony’s, remembered elaborate Halloween pranks where neighborhood children would block the streets with old cars. “My Dad would say, ‘Oye! those darn kids! We had to take those old cars out of the road again!’ He didn’t know that I was one of them!” Another Halloween, she recalled, “my dad dressed in a big long coat and just stood in a corner by the restaurant. We thought it was the bogeyman and started throwing rocks at him.”

More than a dozen speakers took the mic as the sun set, sharing stories with common themes:

- Intertwined families. “We are all related somehow. All cousins,” several commented.

- Strongly shared pride in the community and residents’ accomplishments through the generations. Many speakers paid tribute to the community’s war veterans. “My grand nephew who just finished his basic training, I’m looking forward to his picture being up here,” said third-generation resident David Huizar, gesturing to the Community Center wall decorated with photos of local veterans. “We are still serving; we are Americans.” As well as its athletes. “We had great ball players here,” Huizar continued. One local team nearly went to the Little League World Series. At Torrey Pines High School, “EG was in charge,” remembered Paul Salgado, grandson of Tony Gonzales of Tony’s Jacal. “My class of 223, in that Torrey Pines first graduating class I would say the best athletes in the school at that time were from EG.”

- A tradition of sharing and caring for one another that persists to this day, and will keep La Colonia strong and healthy into the next century. “If somebody didn’t have as much, the rest of the family would help. Or the neighbors would help,” said David Huizar. “We are all family.”

“I want to thank you who have talked about my father this evening, because my dad did so much for the community,” remembered Lucy Garcia, whose father Frank “Pancho” Garcia, donated the property where St. Leo’s Mission was built and still serves La Colonia. Pancho Garcia converted the front part of his home on the southeast corner of Valley and Genevieve into a grocery store in 1927. Next to the market, he built a cantina. “He also used to hang a sheet between his store and the bar and would charge 10 cents for people to watch Roy Rogers movies.”

With 14 children in the family, “We were poor,” said Esther Lopez. Don Pancho Garcia, “would give my mom credit, keep a tab for her, at a time when people didn’t really do that,” she remembered. “And, we used to like it when his freezer gave out, because all his ice cream would melt. So who do you think he would give it to? The family across the street.”

Many La Colonia memories are magical. “In La Colonia,” Lisa Montes noted, “Santa didn’t come down the chimney, he jumped out of an airplane,” and parachuted into the park.

Growing up in Eden Gardens wasn’t all fun and games, though. Early residents were farmers and raised chickens and goats. They helped build one another’s homes. Many guests recalled attending the segregated “Americanization School,” where the children weren’t allowed to speak Spanish, even if that was the only language they knew.

Some challenges went all the way to Rome. Dr. Daniel Rameriz, who teaches about American religions at Claremont Graduate University, confirmed that his grandmother Cipriana Gonzales took on the Pope to keep St. Leo’s open when the archdiocese of San Diego threatened to close the parish. “There were letters from the Pope’s guy in the D.C., the Papal Nuncio, to the Bishop of San Diego, to the Monsignor of Saint James asking about the ‘trouble makers.’ And Cipriana Gonzales’ name was at the top of the list.”

“Well, she won,” he continued. Cipriana had argued that the church was essential to the community of La Colonia. As essential as a beating heart. And the beat goes on.

Centennial Celebration Videos

Eden Gardens Centennial-

Arthur Senteno

Eden Gardens Centennial-

Lucy Garcia

Eden Gardens Centennial-

Esther Lopez

Eden Gardens Centennial-

Daniel Ramirez

Eden Gardens Centennial-

Eddie Huizar

Eden Gardens Centennial-

David Huizar

The Cherokee Who Once Owned Eden Gardens

By Richard Moore, SBC&HS Historian Emeritus

Ned Bushyhead was six years old when his family was forced to relocate from their home in Tennessee to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), where the Cherokee people were being resettled by the US government. His father Jesse, an ordained Baptist minister, set out in September 1838 with his pregnant wife and family, leading a contingent of 950 Cherokees to the new lands. After a delayed and particularly hazardous crossing of the icy Mississippi river in early January 1839, a baby sister to Edward was born. She was named Eliza Missouri, after her mother and the state they had then reached. Finally, the group, which now numbered 898, arrived in Oklahoma in February 1839, settling in an area near the Arkansas border which came to be called Breadtown (after its mission of providing food to subsequent Cherokee arrivals). Six births had been recorded on the journey, including little Eliza.

Breadtown, later known as Baptist Mission, soon had a newspaper, the Cherokee Messenger, started in August 1844. It was the first periodical to be published in the Indian Territory, and 12-year old Ned Bushyhead is believed to have learned the printing business there. The “History of San Diego County” recounts that Ned emigrated in 1850 to California, stopping first at Placerville. A year later he went to Tuolumne County, where he tried his hand at mining for two years. Printing was in his blood, however, and he moved to Calaveras County where he engaged his passion in newspaper publishing until 1868, when he was persuaded to move to San Diego by his then-employer, W. J. Gatewood. The Great Register of Voters shows he signed up to vote here on Sept. 3, 1868.

Ned Bushyhead had second thoughts about the San Diego move. He was skeptical that the newspaper that he and Gatewood started, The San Diego Union, would ever make a go of it. So unconvinced was he that he declined to list his name on the first editions as publisher, substituting instead the name of J. N. Briseno, the office boy. The first issue, published in Old Town, appeared on October 10, 1868. Despite Bushyhead’s initial concerns, the paper became an established newspaper, and adhered to an editorial policy of neutrality.

In June 1873, Bushyhead sold his interest in the paper for $5,000 to pursue other interests.Those other interests included matrimony, and in late 1876 Ned married the widow Helen Cory Nichols of New York. They adopted a daughter, who later died while still young. Helen was something of a mystic, and it is said that she set a place for dinner for her deceased daughter every evening.

Ned Bushyhead threw himself into his new avocations with the same passion and vigor he had as a publisher. From 1875 to 1882 he served as deputy sheriff of San Diego County, and then as sheriff from 1882 to 1886. Not neglecting his adopted city, he was the chief of police of the City of San Diego from 1899 to 1903, and was held in high esteem by the citizenry.

Real estate development in this burgeoning town of San Diego drew many entrepreneurs, Ned Bushyhead among them. One of his ventures was building an Italianate-style mansion as a rental. This house, moved from its original location, is still preserved in San Diego’s Heritage Park next to Old Town.

A look at the San Diego County Recorder’s archives hints at the extent of Bushyhead’s many real estate dealings. The transaction of most interest to us is his purchase of acreage in the square mile of Section 2, Township 14 South, Range 4 West, an area which encompasses most of southern Solana Beach. The original government patent for 160 acres of this land was issued to a Peter Trask from Maine in 1890. This 160 acres was later purchased by Ned Bushyhead, almost certainly as an investment. As was the custom at the time, wives were often recorded as the property owners, and an 1892 assessor’s map shows Mrs. H. C. Bushyhead as the taxable owner.

After Ned’s death in March 1907, his sister Eliza Missouri Alberty, now widowed by her second husband and living in the Cherokee Nation in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, had the responsibility for disposing of Ned’s land. In June 1909, she sold 130 acres of the land which abutted the Stevens’ Molly Glen Ranch for $3,000 to Jennie Cochran Stevens, wife of Edwin Stevens. This 130 acres included all of present-day Eden Gardens. Edwin’s nephew Mark Stevens, active in real estate, had urged Jennie and Edwin to purchase the property. They scraped the money together and did so. Later, Jennie subdivided the land and sold it for a 10-fold profit with the help of Col. Ed Fletcher’s brother-in-law – – but that’s another story.

And the unusual name?? Indian customs led to names based on physical attributes. Ned’s great grandfather, a young Scottish officer with the British army, had come to the Colonies as an Indian agent. He married a Cherokee woman, living the rest of his life among the Cherokees. The young officer was called “Bushyhead” because of his luxuriant curly red hair.

Resources for this article included publications of the San Diego Historical Society and the Oklahoma State Library, and the research of Richard Moore and Richard Schwartzlose of the Solana Beach Civic & Historical Society.

La Escuelita (The Little School)

By Lisa Montes, SBC&HS Historian and Museum Curator

La Colonia de Eden Gardens was the birthplace of my Mother and countless relatives. My family settled here in La Colonia in the early 1920’s because of job opportunities.

My Mother, Carmen Celia Scott, was born in 1929 on Juanita Street, just one street away from where she would attend school and would eventually be married. Spanish was her first language, like that of many of her cousins and friends. Her parents did speak English, but Spanish was the preferred language in the home.

La Colonia de Eden Gardens was a racially segregated community. Mexican American children attended the Americanization school, also known as “La Escuelita” to the La Colonia families.

Photo compliments of Lisa Montes and family

“La Escuelita” was located on Genevieve Street, across from St. Leo’s Mission. Children could not speak their native language at school or they would be punished. I believe this was the birth of Spanglish, because my Mother’s Spanish was not that of a native speaker.

Many of the children attending “La Escuelita” were related by blood, marriage or through baptism. This was because families traveled together to La Colonia from Bisbee, Arizona, Texas, and Santa Ana, California, in search of work and to start a new life. As I look through school photos, it is amazing to see all of the family connections. Solana Beach has a deep and rich history to be cherished!

It wasn’t until high school and segregation had been abolished when my Mother enrolled in Spanish as a “Foreign Language” at San Dieguito High. In fact she shared a funny Spanglish story with me that I would always share with my students. When she was in her Spanish class at San Dieguito, the Teacher asked the students, “How do you say Crackers in Spanish?” Several students raised their hand, along with my Mother. The Teacher picked my Mother and she blurts out, “Crackas!” The La Colonia students laughed! Crackas is Spanglish for Crackers, but the correct term is Galletas. I still find myself referring to crackers as “Crackas” as a fun memory of my Mother.

I was fortunate to see the remnants of La Escuelita here in La Colonia when I would walk with my Mother to church at St. Leo’s on Genevieve Street. We would walk through the empty building and she would share stories of her childhood with me. She loved her teacher Mrs. Clark and would say how kind she was to her. She shared memories of being in class with her cousins and going home to have lunch (because it was the next street over), then running back to school.

Today, much has changed in La Colonia de Eden Gardens, but the memories still remain. There are apartments where “La Escuelita” once stood. The church where my Mother was married is still flourishing. The Tree of Life tiled wall located at La Colonia Community Center – and the Solana Beach Heritage Museum – offer additional glimpses of the history of the families who lived in La Colonia de Eden Gardens.

Boo-Boo had been looking forward to the Historical Society’s Halloween party all month. He had never been to one before, and was excited to dress up in his best white sheet.

Boo-Boo had been looking forward to the Historical Society’s Halloween party all month. He had never been to one before, and was excited to dress up in his best white sheet. Jackie o’Lantern was feeling excited as she made her way to the community center by the sea. It was the earliest Halloween party of the season, and Jackie loved nothing more than dressing up and celebrating with her friends.

Jackie o’Lantern was feeling excited as she made her way to the community center by the sea. It was the earliest Halloween party of the season, and Jackie loved nothing more than dressing up and celebrating with her friends. The Jinx attended the earliest Halloween party of the season, at a community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon and the days might finally start to get chilly. The Jinx was excited to attend his first Halloween party, but he was also nervous. What would he wear? He had no idea what costumes humans wore. He decided to go as himself and flew to the party in a cloud of dark smoke.

The Jinx attended the earliest Halloween party of the season, at a community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon and the days might finally start to get chilly. The Jinx was excited to attend his first Halloween party, but he was also nervous. What would he wear? He had no idea what costumes humans wore. He decided to go as himself and flew to the party in a cloud of dark smoke. Obscuro was getting excited for the upcoming Halloween party. It would be his first one of the season, and he was looking forward to dressing up in his favorite costume. He had white latex skin that made his face look like a mask, so he always stuck out in a crowd. But that was exactly why he loved going to Halloween parties- he loved the opportunity to show off his unique look.

Obscuro was getting excited for the upcoming Halloween party. It would be his first one of the season, and he was looking forward to dressing up in his favorite costume. He had white latex skin that made his face look like a mask, so he always stuck out in a crowd. But that was exactly why he loved going to Halloween parties- he loved the opportunity to show off his unique look. Lucius Morte had never been to a Halloween party before. He had always been too busy tormenting the damned in the 4th level of hell to bother with earthly celebrations. But this year, he was feeling particularly restless and decided to venture out into the world of mortals. He found a community center by the sea that was hosting a Halloween party and decided to attend.

Lucius Morte had never been to a Halloween party before. He had always been too busy tormenting the damned in the 4th level of hell to bother with earthly celebrations. But this year, he was feeling particularly restless and decided to venture out into the world of mortals. He found a community center by the sea that was hosting a Halloween party and decided to attend. Vespera was so excited to go to the Halloween party. It was at a community center by the sea, and it would be her first party in a long time! She had been practicing her mime and charade skills for weeks, and she was determined to show everyone how good she was.

Vespera was so excited to go to the Halloween party. It was at a community center by the sea, and it would be her first party in a long time! She had been practicing her mime and charade skills for weeks, and she was determined to show everyone how good she was. Gourdy Bane was very excited to attend the earliest Halloween party of the season. It was being held at a community center by the sea, and he loved the sound of waves crashing against the shore. When he arrived, he saw that the party was already in full swing. There were pumpkins everywhere, and people were dressed in costumes. Gourdy Bane saw a couple of gourds wearing pirate costumes, and he couldn’t help but laugh. He loved Halloween parties, and he was having a great time dancing to the music and eating candy.

Gourdy Bane was very excited to attend the earliest Halloween party of the season. It was being held at a community center by the sea, and he loved the sound of waves crashing against the shore. When he arrived, he saw that the party was already in full swing. There were pumpkins everywhere, and people were dressed in costumes. Gourdy Bane saw a couple of gourds wearing pirate costumes, and he couldn’t help but laugh. He loved Halloween parties, and he was having a great time dancing to the music and eating candy. Morrigana was very excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and the days were finally starting to get chilly. Morrigana had been working on her Halloween outfit all year long, and she was looking forward to showing it off.

Morrigana was very excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and the days were finally starting to get chilly. Morrigana had been working on her Halloween outfit all year long, and she was looking forward to showing it off. William Wisp had been looking forward to the community center’s Halloween party all month long. It was going to be two days before the full moon, and he loved the smell of fall in the air (cinnamon and pumpkin spice). His Halloween costume was all ready to go, and he was excited to show it off to all of his friends. This year, he was dressed as a pumpkin. His little orange boots matched his little pumpkin body perfectly.

William Wisp had been looking forward to the community center’s Halloween party all month long. It was going to be two days before the full moon, and he loved the smell of fall in the air (cinnamon and pumpkin spice). His Halloween costume was all ready to go, and he was excited to show it off to all of his friends. This year, he was dressed as a pumpkin. His little orange boots matched his little pumpkin body perfectly. Mr. Creepers was all dressed up and ready to go to the community center by the sea for the earliest Halloween party of the season. It had been a long time since he’d been out and about, but he was feeling young at heart and ready to have some fun. He loved the black 1940s coat that he had found at a thrift store and felt confident that he would be the most stylish person at the party.

Mr. Creepers was all dressed up and ready to go to the community center by the sea for the earliest Halloween party of the season. It had been a long time since he’d been out and about, but he was feeling young at heart and ready to have some fun. He loved the black 1940s coat that he had found at a thrift store and felt confident that he would be the most stylish person at the party. The Frankster had always loved Halloween. He loved the costumes, the candy, and most of all, the parties. This year, he was especially excited for the party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and he could feel a tiny bit of a cool autumn breeze in the air.

The Frankster had always loved Halloween. He loved the costumes, the candy, and most of all, the parties. This year, he was especially excited for the party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and he could feel a tiny bit of a cool autumn breeze in the air. Wooblydook was really excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. He had never been to one before, and he was looking forward to kale pulling and making neep lanterns. The party was two days before the full moon, and Wooblydook was hoping it would start to get chilly soon. He loved being out in the cold and feeling his bat-like ears flap in the wind.

Wooblydook was really excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. He had never been to one before, and he was looking forward to kale pulling and making neep lanterns. The party was two days before the full moon, and Wooblydook was hoping it would start to get chilly soon. He loved being out in the cold and feeling his bat-like ears flap in the wind. As the sun began to set, the community center by the sea came to life. Lights flickered on, announcing that the earliest Halloween party of the season was about to start. A golden sun slowly rose in the sky, growing brighter and brighter as it got closer to the horizon. As it reached its peak, people whispered: this sun only came out at night. It was the Midnight Sun.

As the sun began to set, the community center by the sea came to life. Lights flickered on, announcing that the earliest Halloween party of the season was about to start. A golden sun slowly rose in the sky, growing brighter and brighter as it got closer to the horizon. As it reached its peak, people whispered: this sun only came out at night. It was the Midnight Sun.