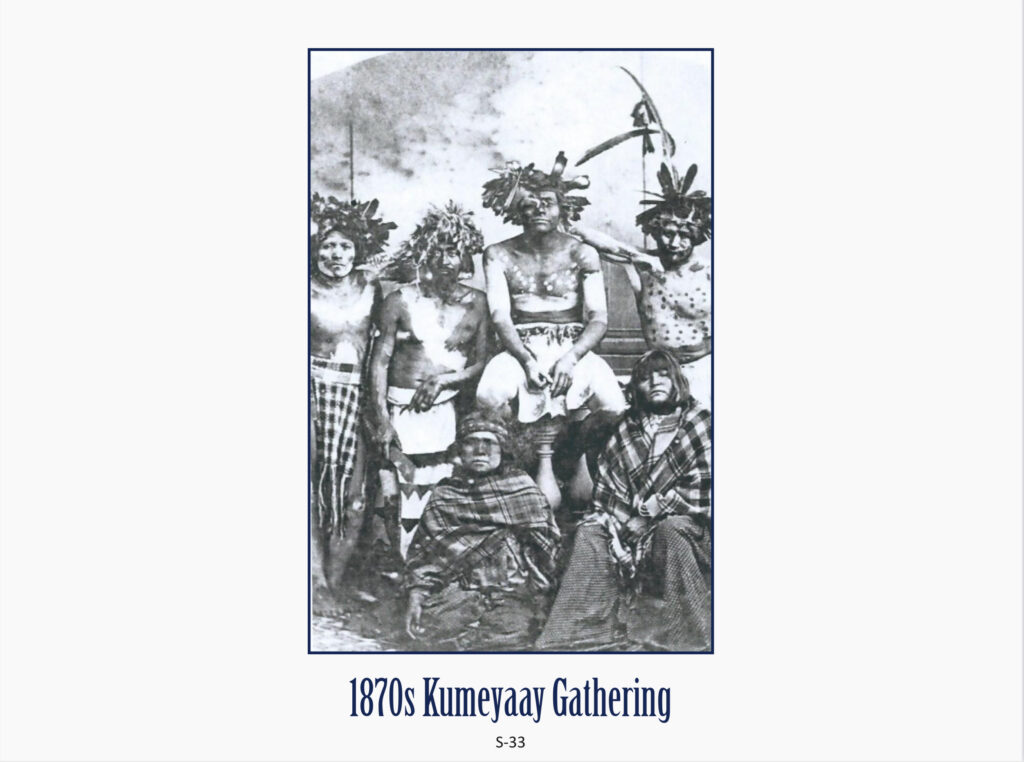

The first known residents of the Solana Beach area migrated here about 9000 BC from Asia across the Alaska land bridge. Now known as the San Dieguitos, they were hunters of large animal such as mastodons, giant bison and camels that grazed in the many marshes and lush grass hillsides of the area. A climate change dried up the marshes and grasslands and many of the large animals perished as their food source disappeared. It is believed a small number migrated south into Mexico who apparently were followed by the San Dieguitos. Evidence of these early settlers can still be found on the bluffs and rolling hills east of the ocean.

The next wave of inhabitants arrived about 7,000 BC are now known as La Jollans. They dwelled in small bands along the coast and around the lagoons, where they collected seafood and gathered seeds.

Around the beginning of the current era, the La Jollans were ousted, or absorbed, by a new group of immigrants from the Colorado River area. Known for almost three hundred years by their Spanish name, Diegueños, today they are referred to as Kumeyaay-Ipai. The Kumeyaay-Ipai fished and foraged along the coast, and gathered acorns, pinon nuts and other edibles in the mountains.

The Spanish arrived in 1769 led by Don Gaspar de Portola. Portola’s charge was to press north from San Diego to Monterey Bay establishing a series of missions along the way. He was accompanied by Franciscan padres whose job it was to convert the local Indians. Traveling between the San Diego and Monterey missions, the Portola party established a trail known as “El Camino Real.” In the Solana Beach area, the Spanish traveled inland to avoid the many marshes and inlets near the coast. El Camino Real crossed at Conley’s corners on Via de la Valle which is now the east end of the Polo Field.

Control of the area passed to Mexico when it gained independence from Spain in 1821. Many of the inhabitants were sons and grandsons of the original Spanish settlers who became influential in government and were owners of enormous ranchos. Many thousands of acres in what is now San Diego County became privately owned during the Mexican regime. The then current mayor of the City of San Diego, Don Juan Maria Osuna, claimed the 8800 acres known as Rancho San Dieguito in 1836. His eldest son, Leandro, lived in a three-room adobe off today’s Via de la Valle near the Rancho Santa Fe village center. It has undergone a second restoration by the Rancho Santa Fe Association. In 1845 Don Juan Osuna built his own adobe about a mile west on Via de La Valle, which was restored in 1923 for Bing Crosby by Lilian Rice

Following the Mexican War with the United States, California became a U.S. territory, and on September 9, 1850, was admitted to the Union. Until the 1860s and the gradual influx of the Anglos, the Californios (early Mexican, large land owners) continued to dominate life in the Solana Beach area. The County of San Diego was established by the State Legislature on February 18, 1850. The population numbered 790. Records show that the first American homesteader in the vast San Luis Rey district, was William A. Ewing, who took up 180 acres in the San Dieguito River valley in 1862.

“Grandpa” Frank Knowles came to the San Dieguito area in 1885. Before Knowles died in the 1940s, he shared memories of a few Indians living on the San Elijo Lagoon at that time. He lived to be 104 years of age. The main area known as Solana Beach was originally called Lockwood Mesa and was uninhabited until 1908 when the first two ranches were established by the George Jones family. Chief crops were grain and lima beans.

The oldest house in Solana Beach is the Stevens House, built in 1887 and originally located on the Molly Glen Ranch. Henry and Belle Sandford of Del Mar established the ten-acre ranch on the south slopes of Solana Beach. It was located on the current site of the Del Mar Downs development. In 1891 the ranch was bought by Susan Stevens, daughter of James and Susannah Stevens, for whom Stevens Street and Stevens Creek were later named. The Stevens were originally from New York, but later moved to Michigan and then North Dakota, where James West Stevens was a State Senator in the third legislature of that state (1892-1896). They came to California in early 1896, with their son Edwin following a year later. In 1898 Susan sold the ranch to her parents.

“Grandma Stevens,” as Susannah was known, was a celebrity when she reached her 105th birthday. By the time she had turned 100, she had been interviewed and photographed by newspapers from Los Angeles and San Diego. She and James celebrated their 60th anniversary with a big party on the Del Mar beach in 1906. James died in 1907 and Susannah Stevens lived in the ranch house until her death in 1927, a few days short of her 106th birthday.

After Susannah’s death, Edwin and his wife Jennie lived in the house until Ed’s death in 1935. They speculated in real estate, and with Col. Ed Fletcher’s brother-in-law Eugene Batchelder, developed the adjacent 160 acres now known as La Colonia de Eden Gardens. The house itself changed hands at least twice after Jennie’s death in 1940. The final owners found old 1890-era newspapers in the walls when they lived there. The Stevens House today is in La Colonia Park and houses the Solana Beach Heritage Museum, which is open by an appointment for a tour by any group of one or more. Email solanabeachhistoricalsociety@gmail.com to schedule.

Lake Hodges Spurs Development

The area encompassing Solana Beach began to develop rapidly when Lake Hodges Dam was built in 1918. The creation of the 12,000-acre Santa Fe Irrigation District in 1918 ensured that the area from Rancho Santa Fe through Solana Beach would prosper and expand. The coastline from Solana Beach to Oceanside began to boom in the early 1920s. In 1922 Colonel Ed Fletcher, an early community leader and developer, purchased 201 acres at $200 per acre from farmer George H. Jones to develop the town of Solana Beach. Fletcher’s goal was for his new community to be the regional commercial center for Del Mar, Rancho Santa Fe and Solana Beach. The goal was never realized when the former two communities overturned the original severe restrictions imposed on commercial development in those towns. Nevertheless Solana Beach grew rapidly paralleling the development of the entire county during the 1924-29 period.

The community was named by Fletcher’s brother-in-law, E. C. Batchelder. After Fletcher subdivided his land, Batchelder was asked to come up with options for naming the community. “Solana Beach” was selected by the men, supposedly after discussion with “Spanish authorities.” The name translates to “sunny” beach.

But there was no way to get to the beach then except by scrambling down a cliff, or walking around the bluffs from one of the two lagoons flanking the community. To create beach access, hydraulic water pressure was used to break up the hard pack and create a notch in the bluffs above the beach. This took one man three months with a fire hose, using water that was coming over the spillway at Lake Hodges Dam. The loose sand was scooped up by steam shovel and trucked to the surf line where it was washed away. The beach was opened with great fanfare, including horse races on July 4th, 1924.

For his “commercial center” Fletcher opened the Bank of Solana Beach, which he subsequently sold to the Bank of America. Other businesses provided by Fletcher were a train station, a Ford agency/garage, a grocery store and a hotel. This prompted the development of many additional businesses on the Plaza, Highway 101 and Cedros Ave. When the depression hit in 1929, Fletcher lost all the buildings noted above and was forced to sell half of real estate holdings in the downtown area plus 800 contiguous acres running to Rancho Santa Fe.

The depression stifled growth in Solana Beach. The price of lots tumbled and land reverted to the Santa Fe Irrigation District for lack of tax payment. For almost a decade, progress was at a standstill. With the approach of World War II, the community began to stir. However, it was not until the early 1950s that the area reached the stage of development that had been predicted for the 1930s.

Additional information on the development of the community can be found in two books published by the Solana Beach Civic and Historical Society. Click here to buy “La Colonia and Solana Beach: Spring Up from Colonel Ed Fletcher’s Running Water” and/or “Early Solana Beach: Recollections by George C. Wilkens and Robert Chuckles Hernandez as told to Jim Nelson.”

Copies also may be purchased obtained at Tony’s Jacal Restaurant.

La Colonia, the older of the two communities, was developed in 1919/20 for Mexican workers who tended the large citrus groves in Rancho Santa Fe. In creating a subsequent 1923 subdivision, Eugene Batchelder registered the name Eden Gardens. In a further expansion in 1944 the name reverted to La Colonia and today is referred to as La Colonia de Eden Gardens.

La Colonia, the older of the two communities, was developed in 1919/20 for Mexican workers who tended the large citrus groves in Rancho Santa Fe. In creating a subsequent 1923 subdivision, Eugene Batchelder registered the name Eden Gardens. In a further expansion in 1944 the name reverted to La Colonia and today is referred to as La Colonia de Eden Gardens.

Solana Beach played a strategic role in defending the Pacific Coast from the Japanese during World War II. Learn about Wartime Solana Beach.

After World War II, the Solana Beach community began to grow. The Chamber of Commerce was formed. A sanitation district and a fire district were created. For a 10-year period between 1950 and 1960, the community underwent tremendous growth. The Bill Jack plant (1949) brought industry into the area and private contractors built a number of homes. Marview Heights, land originally owned by the Santa Fe Irrigation District and later sold as individual homes by Fred Howland Ford and his brother, gave impetus to local residential development.

The market collapsed in 1959-60 and it was not until late 1967 that the trend reversed. Paul Tchang, a San Diego builder, constructed almost 100 premium homes in Solana Beach by 1969. Thirty-three more were built in 1970, and 500 more from 1971 to 1977. Lomas Santa Fe completed their golf course and opened the sale of lots in Isla Verde in 1968. This signaled the beginning of a real estate boom which lasted well into the 80s and 90s. After a brief interval in the mid 90s, real estate sales were once again on the rise.

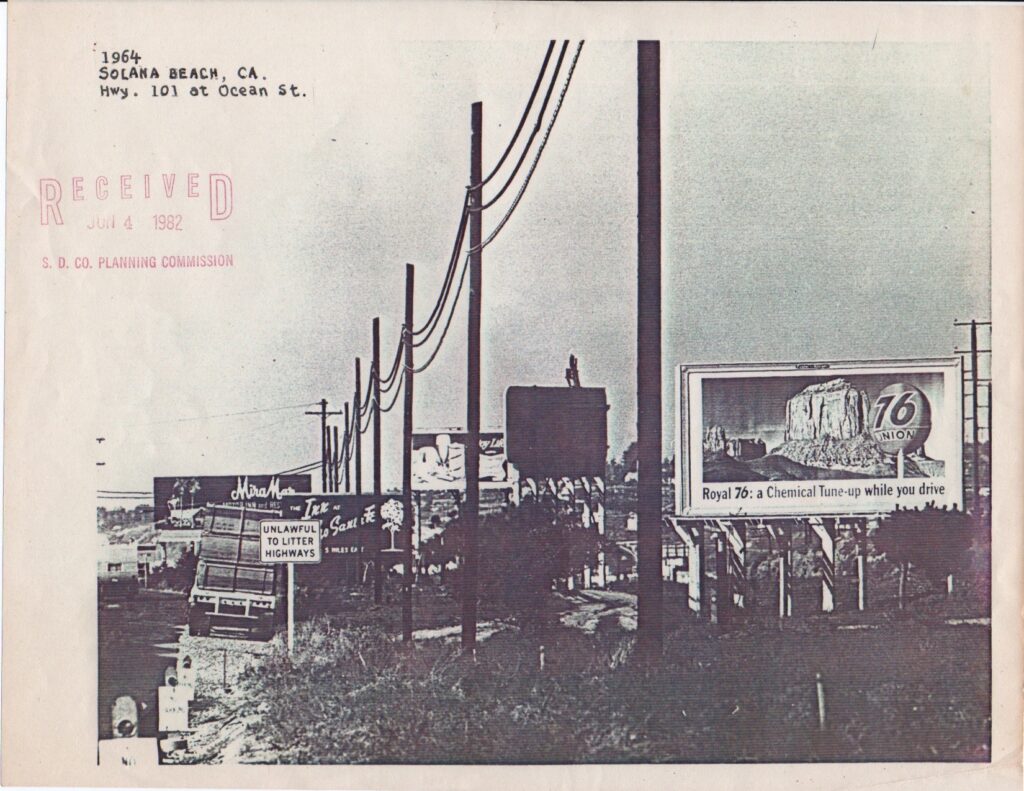

As the community progressed, additional attention was given to civic beautification. The Solana Beach Women’s Civic Club, founded in 1953 and predecessor to the Civic & Historical Society, had succeeded by 1971 in having unsightly billboards removed from along Highway 101 through town.

In 1973, the club obtained lease of the Western section of the railroad right-of-way and planted 450 Torrey and Aleppo pints, hand watering them with the help of the Boy Scouts until funds were raised for in-ground irrigation. The Club also spurred creation of a walking/running trail, which grew in popularity — as did the trees — for the next 20 years.

During this period, the Women’s Civic Club also fostered renovation of the central plaza, installation of the “Sun Burst Fountain,” and posting of welcome signs at City entry-points.

The City of Solana Beach was incorporated in 1986 and included the original neighborhood of La Colonia de Eden Gardens. The City Charter provides a Council-City Manager form of government, with the Mayor’s position rotating among the Council members. Click here to view video discussions with Marion Dodson and other past Council-members.

The Women’s Civic Club was reorganized as the Solana Beach Civic & Historical Society in 1989.

Recent decades saw creation of the Cedros Design District, building of the Solana Beach train station, formation of the 101 Merchants Association, construction of a new joint-use library, and the influx of many new businesses. In 1995 the Santa Fe train station was moved from Del Mar to a new station in Solana Beach. In 1999 the North County Transit District, operator of the “Coaster” commuter train, and the City of Solana Beach completed a $25-million project to lower the train tracks below grade level under Lomas Santa Fe Drive.

The “big dig,” as it became known, required building temporary “shoefly” railroad tracks through the now popular, pine-shaded walking path along Highway 101. Members of the Civic and Historical Society — successor to the Women’s Civic Club — again rallied, with the City, to support an “Adopt a Tree” program. After a a shaky start, the effort ultimately resulted in the relocation and replanting of 361 trees to residential gardens and commercial landscapes. Fifteen trees were saved and, in 1997, eight were boxed and stored along Hwy. 101 for replanting after the “big dig” was completed.

Meanwhile, plans progressed for the “Coastal Rail Trail” that now sits above and beside the 1.8 mile rail corridor. In 2002, the Society raised funds to finally replant the eight boxed trees, creating the Torrey Grove near the northern border of the City. Later in the decade, the Society (and many of its members) donated funds to preserve the open space from commercial development, with a capstone donation coming from the Harbaugh Family Trust. In February 2020, the shady Torrey Grove and Coastal Rail Trail were officially linked with Harbaugh Seaside Trails, merging with the expanding San Elijo Lagoon trail system and northward into Cardiff-by-the-Sea and Encinitas.

Solana Beach Today

More than 13,000 residents call this four-square-mile beach community their home. The Pacific Ocean is to the west; the City of Encinitas to the north, and the City of Del Mar to the south. The unincorporated village of Rancho Santa Fe is located on the east side. Property values in this upscale community have appreciated significantly since incorporation. The business community has equally enjoyed the prosperity of a healthy economy. Solana Beach is the home for many artisans, high-tech businesses and professionals.

The elementary school district is composed of eight elementary schools, two of which are within the City limits. Earl Warren Middle School is under the administration of the San Dieguito Union High School district. Both the middle school and Skyline Elementary School have been completely rebuilt in recent years. High school students in the area generally attend Torrey Pines High School or Canyon Crest Academy, both located to the southeast of Solana Beach in San Diego, or San Dieguito Academy, located in Encinitas. Additionally, there are several private schools in Solana Beach.

The City has two community centers, Fletcher Cove and La Colonia. The Fletcher Cove Community Center, originally a Civilian Conservation Corps barracks, was moved from Vista to Solana Beach in 1944. Some 68 years later, it was It was renovated and reopened for community events in a three-phase project that included extensive landscaping and updates to the adjacent beach access facilities and park.

Ceramic artworks by local artist Betsy Schulz line curved paths to the sea at the Cove, as well as both the south and north entries to the Coastal Rail Trail. Ms. Schulz’s contributions to the City’s public art installations also include the dramatic Fire Wall sculpture at the Fire Station, flanked by a native garden planted by the SeaWeeders Garden Club of Solana Beach.

The Community Center at La Colonia was dedicated on May 5, 1991. Program activities in the centers include adult education classes and meeting places for numerous community groups. In November 1996 the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department opened an office in the La Colonia Park Community Center. In 2007, the city came up with a Master Plan for the whole of La Colonia Park, envisioning elements such as the skate park, an expanded tot lot and a courtyard honoring veterans — which was completed in 2016.

After the city’s anticipated funding source was shut down at the state level, the city had to tackle the Master Plan piecemeal. The skate park remained a priority among residents and an enthusiastic local skating community. A $5,000 donation from the Tony Hawk Foundation kicked off the fund-raising project. From there, the City received a $100,000 Neighborhood Reinvestment Program grant from the county, as well as donations from the Surfing Madonna Oceans Project, the Coastal Communities Foundation and a $10,000 gift from the Civic & Historical Society. The Parks and Recreation Commission also raised money through fundraisers at Culture Brewing and the Fire Department hosted a pancake breakfast. Funding for the approximately $1.1 million project was completed from the city’s Capital Improvement Program Fund.

Project architects — Van Dyke Landscape Architects — gathered input from local skaters for park features, which include a wave-like donor wall displaying the names of individuals, families and businesses that contributed $500 or more. Adjacent to the park is a small basketball court and a free-standing nano grid, called EnegiPlant, with WiFi and ports for phone-charging.

To help celebrate the skatepark opening in April 2019, the Society sponsored a competitive challenge for local 6th, 7th and 8th graders — no helmets required. Students were invited to participate in two contests:

- Create artwork for a skateboard deck that conveyed the importance of the new skatepark to the community and the athletes who will use it, as well as the importance of its location in La Colonia de Eden Gardens, Solana Beach’s first neighborhood. Or,

- Develop a video documentary on the long history of the skatepark, from idea to the grand opening.

In the video category, Cleo Krems, then a Skyline School 6th grader, took home the $250 first place prize. Click here to view her winning report. A team of Earl Warren Middle School 8th graders each earned $100 runners-up prizes — Danika Blease, Tanner Phillips and Robert Schmidling.

In the deck design competition, Camden Cassara, then a 7th grader at Earl Warren, was the first place winner. Runners-up were Avery Austin, Lauren Prior and Kathryn Reese, then 7th graders at Earl Warren, as well as Cristina Milne, then in grade 7 at Saint James Academy. Each received $100 prizes.

Contest judges, who assessed more than 50 entries, also awarded $50 special recognition deck-art prizes to two more Earl Warren 7th graders: Dylan Flynn, for a clever photo montage that incorporated some of Solana Beach’s iconic curved rooflines, and Eli Shiah, for a catchy tagline: “Where the ride meets the tide.”

Cedros Design District

The South Cedros area of the City has been developed as an upscale design district, but its cultural heart remains the world famous Belly Up tavern, established in 1974. Later developed as a concert hall, the Belly Up is consistently acclaimed as one of San Diego’s best live music venues. Through the years (check out the club’s timeline), it has featured artists as diverse and renowned as Bo Diddley, Willie Nelson, Tom Jones and The Rolling Stones and The Red Hot Chili Peppers, to name just a very few.

The Belly Up celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2024. Learn more about it’s fabled history.

The Day the Music Died

On March 19, 2020, the Belly Up went silent. The beaches were closed. The beaches were closed! Hiking trails were closed. How can nature be “closed?”

An invisible virus called COVID-19 created global pandemic that nobody, at the time, knew how to tame except through avoidance. Of oneself. “Don’t touch your face.” And then of avoidance of one another. Stay home. Shut down. Deep clean. Disinfect. We were warned that even walking by someone on the beach might be a moment of infection. Schools closed and classrooms were replaced by online Zoom sessions, even for kinder-garteners.

Vaccines were rapidly created. Beaches reopened; masking became optional. Life returned to something like normal after about two years, But the COVID era still is unfolding in our commercial district, where work patterns disrupted by the pandemic have reshaped the office, retail and restaurant scene.

Boo-Boo had been looking forward to the Historical Society’s Halloween party all month. He had never been to one before, and was excited to dress up in his best white sheet.

Boo-Boo had been looking forward to the Historical Society’s Halloween party all month. He had never been to one before, and was excited to dress up in his best white sheet. Jackie o’Lantern was feeling excited as she made her way to the community center by the sea. It was the earliest Halloween party of the season, and Jackie loved nothing more than dressing up and celebrating with her friends.

Jackie o’Lantern was feeling excited as she made her way to the community center by the sea. It was the earliest Halloween party of the season, and Jackie loved nothing more than dressing up and celebrating with her friends. The Jinx attended the earliest Halloween party of the season, at a community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon and the days might finally start to get chilly. The Jinx was excited to attend his first Halloween party, but he was also nervous. What would he wear? He had no idea what costumes humans wore. He decided to go as himself and flew to the party in a cloud of dark smoke.

The Jinx attended the earliest Halloween party of the season, at a community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon and the days might finally start to get chilly. The Jinx was excited to attend his first Halloween party, but he was also nervous. What would he wear? He had no idea what costumes humans wore. He decided to go as himself and flew to the party in a cloud of dark smoke. Obscuro was getting excited for the upcoming Halloween party. It would be his first one of the season, and he was looking forward to dressing up in his favorite costume. He had white latex skin that made his face look like a mask, so he always stuck out in a crowd. But that was exactly why he loved going to Halloween parties- he loved the opportunity to show off his unique look.

Obscuro was getting excited for the upcoming Halloween party. It would be his first one of the season, and he was looking forward to dressing up in his favorite costume. He had white latex skin that made his face look like a mask, so he always stuck out in a crowd. But that was exactly why he loved going to Halloween parties- he loved the opportunity to show off his unique look. Lucius Morte had never been to a Halloween party before. He had always been too busy tormenting the damned in the 4th level of hell to bother with earthly celebrations. But this year, he was feeling particularly restless and decided to venture out into the world of mortals. He found a community center by the sea that was hosting a Halloween party and decided to attend.

Lucius Morte had never been to a Halloween party before. He had always been too busy tormenting the damned in the 4th level of hell to bother with earthly celebrations. But this year, he was feeling particularly restless and decided to venture out into the world of mortals. He found a community center by the sea that was hosting a Halloween party and decided to attend. Vespera was so excited to go to the Halloween party. It was at a community center by the sea, and it would be her first party in a long time! She had been practicing her mime and charade skills for weeks, and she was determined to show everyone how good she was.

Vespera was so excited to go to the Halloween party. It was at a community center by the sea, and it would be her first party in a long time! She had been practicing her mime and charade skills for weeks, and she was determined to show everyone how good she was. Gourdy Bane was very excited to attend the earliest Halloween party of the season. It was being held at a community center by the sea, and he loved the sound of waves crashing against the shore. When he arrived, he saw that the party was already in full swing. There were pumpkins everywhere, and people were dressed in costumes. Gourdy Bane saw a couple of gourds wearing pirate costumes, and he couldn’t help but laugh. He loved Halloween parties, and he was having a great time dancing to the music and eating candy.

Gourdy Bane was very excited to attend the earliest Halloween party of the season. It was being held at a community center by the sea, and he loved the sound of waves crashing against the shore. When he arrived, he saw that the party was already in full swing. There were pumpkins everywhere, and people were dressed in costumes. Gourdy Bane saw a couple of gourds wearing pirate costumes, and he couldn’t help but laugh. He loved Halloween parties, and he was having a great time dancing to the music and eating candy. Morrigana was very excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and the days were finally starting to get chilly. Morrigana had been working on her Halloween outfit all year long, and she was looking forward to showing it off.

Morrigana was very excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and the days were finally starting to get chilly. Morrigana had been working on her Halloween outfit all year long, and she was looking forward to showing it off. William Wisp had been looking forward to the community center’s Halloween party all month long. It was going to be two days before the full moon, and he loved the smell of fall in the air (cinnamon and pumpkin spice). His Halloween costume was all ready to go, and he was excited to show it off to all of his friends. This year, he was dressed as a pumpkin. His little orange boots matched his little pumpkin body perfectly.

William Wisp had been looking forward to the community center’s Halloween party all month long. It was going to be two days before the full moon, and he loved the smell of fall in the air (cinnamon and pumpkin spice). His Halloween costume was all ready to go, and he was excited to show it off to all of his friends. This year, he was dressed as a pumpkin. His little orange boots matched his little pumpkin body perfectly. Mr. Creepers was all dressed up and ready to go to the community center by the sea for the earliest Halloween party of the season. It had been a long time since he’d been out and about, but he was feeling young at heart and ready to have some fun. He loved the black 1940s coat that he had found at a thrift store and felt confident that he would be the most stylish person at the party.

Mr. Creepers was all dressed up and ready to go to the community center by the sea for the earliest Halloween party of the season. It had been a long time since he’d been out and about, but he was feeling young at heart and ready to have some fun. He loved the black 1940s coat that he had found at a thrift store and felt confident that he would be the most stylish person at the party. The Frankster had always loved Halloween. He loved the costumes, the candy, and most of all, the parties. This year, he was especially excited for the party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and he could feel a tiny bit of a cool autumn breeze in the air.

The Frankster had always loved Halloween. He loved the costumes, the candy, and most of all, the parties. This year, he was especially excited for the party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and he could feel a tiny bit of a cool autumn breeze in the air. Wooblydook was really excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. He had never been to one before, and he was looking forward to kale pulling and making neep lanterns. The party was two days before the full moon, and Wooblydook was hoping it would start to get chilly soon. He loved being out in the cold and feeling his bat-like ears flap in the wind.

Wooblydook was really excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. He had never been to one before, and he was looking forward to kale pulling and making neep lanterns. The party was two days before the full moon, and Wooblydook was hoping it would start to get chilly soon. He loved being out in the cold and feeling his bat-like ears flap in the wind. As the sun began to set, the community center by the sea came to life. Lights flickered on, announcing that the earliest Halloween party of the season was about to start. A golden sun slowly rose in the sky, growing brighter and brighter as it got closer to the horizon. As it reached its peak, people whispered: this sun only came out at night. It was the Midnight Sun.

As the sun began to set, the community center by the sea came to life. Lights flickered on, announcing that the earliest Halloween party of the season was about to start. A golden sun slowly rose in the sky, growing brighter and brighter as it got closer to the horizon. As it reached its peak, people whispered: this sun only came out at night. It was the Midnight Sun.