WWII Army Nurse Crossed Country 26 Times on Hospital Trains Before Meeting her Husband — a Former Stalag 4A Prisoner of War

Adapted from articles by Lillian Cox on April 14, 2006 and by Marcia Manna, November 11, 2006 in the San Diego Union Tribune and with contributions from the Disselhorst family

Trudy Disselhorst was 21 in 1945, and newly out of basic training at Ft. Lewis, Washington, when she was assigned to work on hospital trains transporting sick and wounded soldiers returning home from World War II.

In those days, she was Lt. Trudy Zeller of the Army Corps of Nurses and based at Camp Haan in Riverside. Trudy greeted patients arriving from San Diego, Long Beach and Los Angeles and sorted them into train cars according to the hospital that would be closest to their hometowns and families.

She traveled coast-to-coast 26 times delivering combat veterans from both the South Pacific and European theaters. At each stop, a hospital car was detached from the train until all cars were gone. Then the staff would “dead head” back to Riverside.

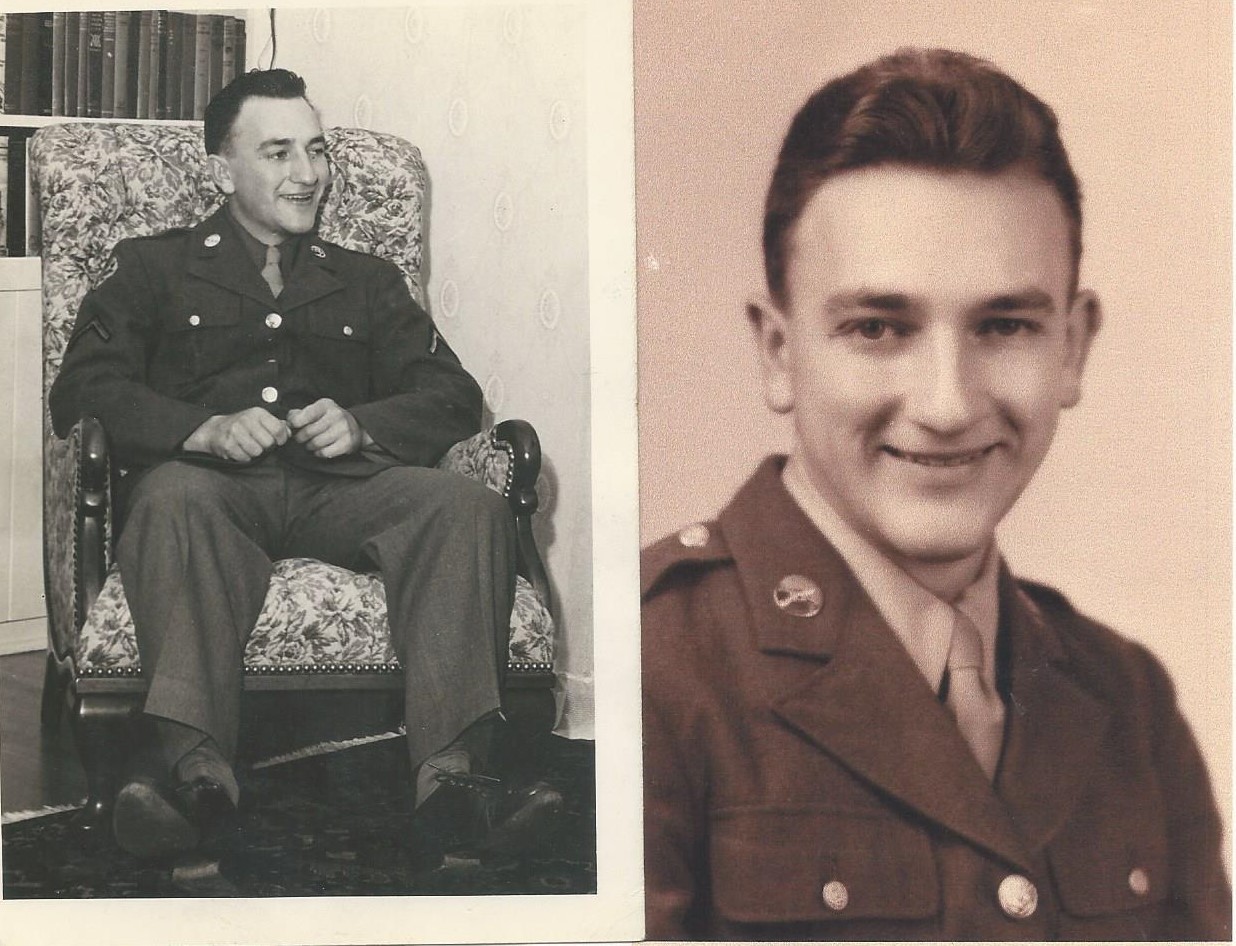

After being discharged from the Army in 1946, Trudy continued her nursing career at the Swedish Hospital in Seattle Washington. She subsequently married Byron Disselhorst, a former World War II Prisoner of War, in Berkeley in1953.

Byron was born on a farm in Quincy, Illinois on October 298, 1923. He moved to Portland, Oregon in 1936, where he graduated from high school and started college at Oregon State. When the war started, and he enlisted as an infantryman and was assigned to the U. S. 7thAlsace region of France and transported via boxcar to Dresden, Germany.

Byron was confined to a boxcar for days while on his way to a work camp. “We could either stand or sit,” Byron told the San Diego Union Tribune in 2006, “but not lay down.” At the Stalag 4A camp, he was assigned pick-and-shovel work. Rations were a bowl of watered soup and a slice of bread per day. Everyone had lice. When he was liberated in May, five months after his capture, Byron weighed about 90 pounds and was still wearing the clothes he was captured in.

After the Germans released the POW’s, “We had to do whatever we could to survive, ” he told the Tribune. “They had horses that pulled wagons and a couple of them got killed by artillery fire. We cut meat off the dead horses and cooked it and ate it. That’s how hungry we were.”

Prior to capture by the German Army, Byron was awarded a Bronze Star. After the war, he returned to Oregon State University and graduated with a BS in Chemical Engineering in 1947. In 1951, he began work at the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory in Livermore, CA. He also served in the Air Force Reserve from 1951 to 1962, achieving the rank of Captain.

After marrying Trudy, he worked as an engineer at General Atomics from 1959 to 1991. They moved to Solana Beach in 1959, had a house built on Nardo Ave. and had four children. One of nine grandchildren, Rebecca Spencer, took a similar path into military medical care. An honors nursing student in the ROTC program at Azusa Pacific University, Rebecca was commissioned in the Army at Ft. Lewis in August of 2016.

Trudy retired as a private duty nurse in 1986. During retirement, she stayed active in the Scraps & Prayers sewing group at Bethlehem Lutheran Church in Encinitas and with reading programs at Solana Vista School. Byron also volunteered with the church, as well as as a Scout leader and baseball coach.

In 2006, Trudy was also one of 24 participants in Legacies, a cross-generational project sponsored by the Solana Beach Civic & Historical Society and produced by the non-profit StoryArts, Inc. Trudy was paired with Stephanie Thurston, 15, then a sophomore at Canyon Crest Academy.

“Few people know that these hospital trains existed,” Stephanie reported. “Mrs. Disselhorst … helped these soldiers return home to a life of normalcy. Coming from a sheltered background, it must have been so hard, psychologically, for her to see what they went through.”

“A lot of the patients were not very mobile,” Trudy told Stephanie. “Trips with amputees were especially hard because they were in pain all night long.” In addition to battle wounds, troops being transported had illnesses and injuries related to where they had served in the war, she said. Common diseases incurred in the South Pacific were malaria, jungle rot, elephantiasis and osteomyelitis. Soldiers who had fought in Europe, many of them Battle of the Bulge survivors, suffered from frozen feet.

Countless veterans were treated for shell shock, now called post-traumatic stress disorder. The night of V-J Day, the train was stopped in Gallup, N.M,” Trudy said. “I saw a patient outside dressed in uniform. It was pitch black. I said, What are you doing out there?’He replied, ‘I’m going to celebrate.’ Since there was nobody to help me, I had to sweet talk him into coming inside to celebrate.

“He was a psychiatric patient who was wearing the uniform of one of the corpsmen. They had left the door unguarded and were at the other end of the train playing poker.”

Trudy’s work on the hospital train took her to parts of the country that were new to her.

“The train was delayed in Asheville, N.C.,” she recalled. “It was close to Christmas, so I left to go shopping. I got on a bus and sat in the back next to a black woman. The bus driver yelled, ‘You! Lady! Come in front!’ I didn’t know what he wanted. I was in fulI uniform. He pointed to a sign that read, ‘Colored Only in Back.”‘

When she exited, Trudy defiantly left by the back door.

Byron Frederick Disselhorst passed away suddenly on the morning of July 11, 2011, at the La Costa Glen, Carlsbad, retirement community where he and Trudy then resided. He was 88 and had been married to Trudy for 58 years. Eleanor Gertrude “Trudy” (Zeller) Disselhorst passed away on July 22, 2013, after a battle with pancreatic cancer. She was 89.

Excerpted from “Legacies: The Solana Beach Youth/Elder Story Art Project”

Nursing Across America: Trudy’s Story

World War II started December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor Day.

I remember where I was. I had just started my nurses training and I was with a friend in a bowling alley. It was a Sunday afternoon. We weren’t on the floors at the hospital much yet. We were still studying. But after the war started, we were on the floors a lot, because most all of our nurses, supervisors and doctors left to go overseas.

Then, later, the cadet nurse program came in. They needed more nurses in the military. My girlfriend Phyllis and I signed up for the Navy. After our basic training in Fort Lewis we were sent to the Dewitt General Hospital in Auburn, California, above Sacramento. We immediately got all of these patients from the Battle of the Bulge with their frozen feet and arms. And there were some fliers who had been shot-down.

I was later transferred to a hospital train unit. We took the patients who came into the ports at San Diego and Long Beach that had come back from the South Pacific to the hospitals closest to their homes. They had three tiers of bunks in each train car. They were all set up just like a hospital. We had a head nurse and shifts. We worked twelve-hour shifts and were each as signed one car, or maybe two. Each car was going to a certain place.

Sometimes we would take them to Ogden, Utah, because that was the amputee site. That was the hardest trip, because we had a carload of amputees. They were in pain, and we would be up all night giving them pain shots. That was hard. It was a specialty hospital where they got their prostheses. We would pick up a load on the East Coast, too, and then come back. We had a war on both sides—the Pacific and the Atlantic.

I was so young. You somehow take it in stride when you’re twenty-one years old. I made twenty-six round trips across the United States, while nursing our boys. So all together I went across fifty-two times.

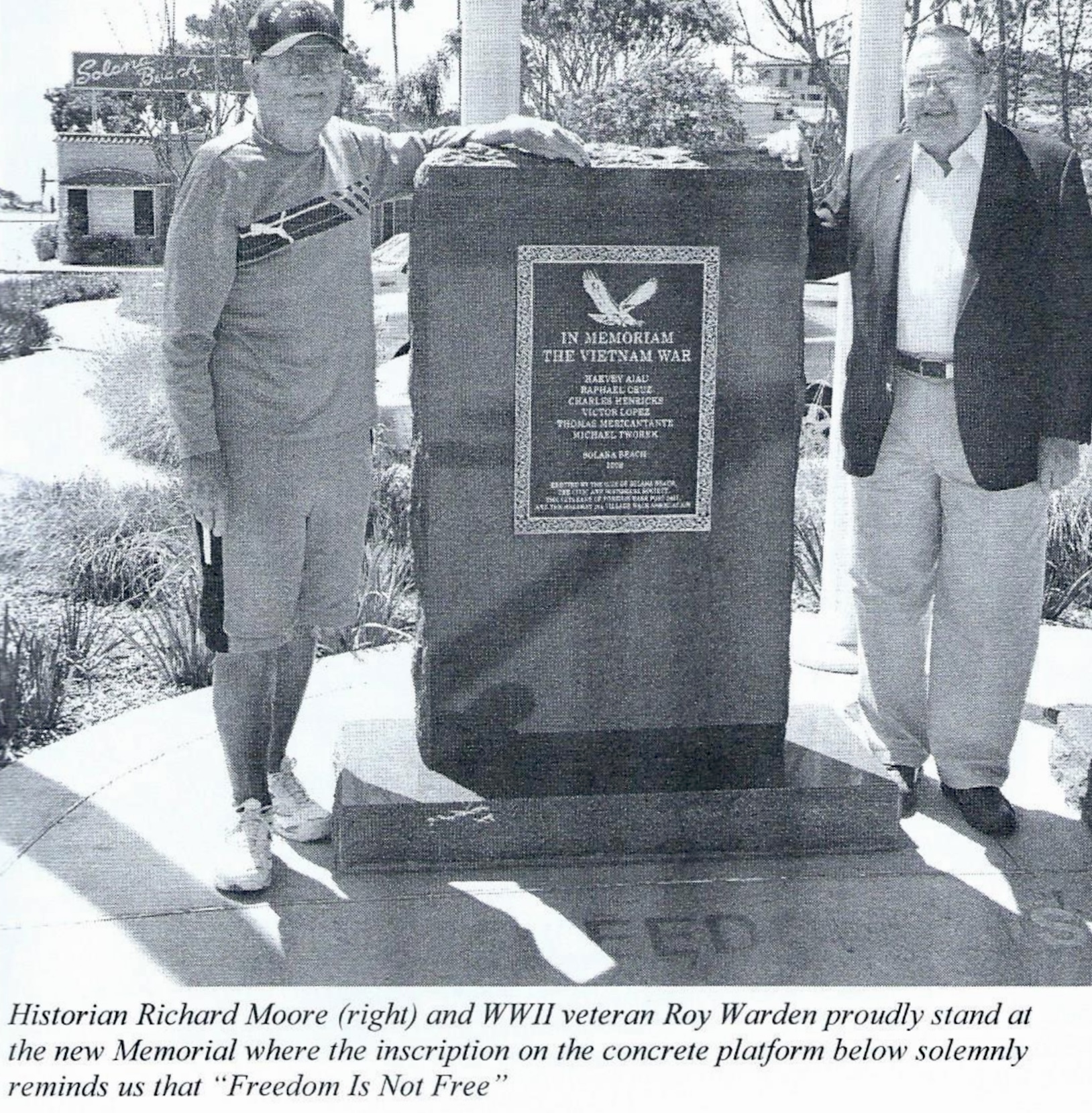

Vietnam Veterans War Memorial Dedicated in 2009

Years after the Solana Beach city Council approved adding a third memorial to war veterans, area service members who where killed in the Vietnam conflict finally were honored with the installation of a plinth and plaque next to the World War II memorial at the northeast corner of Plaza and Highway 101. More than 100 people, including family and friends of the deceased, attended the dedication of the memorial on March 25, 2009.

The memorial honors Vietnam Veterans Harvey Aiau (1930-1970), Raphael Cruz (1935-1963), Charles Drayton Henricks (1942-1969), Victor “Chief” Lopez (1947-1969), Thomas Mericantante (1949-1968) and Joseph Michael Tworek (1946-1971) — all of whom left for the war from Solana Beach, where they had either grown up or moved to later in life. The fallen represented all branches of the armed services. All were killed in battles in Vietnam except Tworek, a decorated Army helicopter pilot who returned from the war in 1969 and was assigned to Fort Rucker, Alabama, as an advanced instrument instructor. He was killed in a mid-air night collision during a training mission.

For the dedication of the memorial, Society historian Richard Moore compiled “The Service Eternal”, a remembrance of all of the Solana Beach-area servicemen killed in World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War. Short biographies of the six Vietnam, as well as eight World War II veterans, were read during the ceremony.

The dedication was hosted by the City of Solana Beach, the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) Post 5431 and the Civic and Historical Society. But selecting a site for the memorial generated perhaps unexpected controversy. In November 2005, according to press reports, Council had approved — in a 3-2 vote — for the memorial to be located at a viewpoint just southwest of the Fletcher Cover Community Center. More than a dozen residents had come to the meeting to express their support for the memorial site, including Society-member Eleanor “Trudy” Disselhorst, who had criss-crossed the country during World War II as a lieutenant with he Army Corps of Nurses. However, others argued that the chosen site was a bit out of the way and would be under-visited.

Attending another Council meeting in February of 2006, World War II-veteran Roy Warden, argued that members of the local VFW preferred to have the additional memorial placed at La Colonia Park, the traditional gathering spot for Memorial and Veterans Day commemorative ceremonies and site of other existing memorials. In the end, it was decided to locate the Vietnam memorial next to another existing World War II memorial which had been relocated from the Plaza center divider during a prior street redesign. Both plinths and plaques sit atop a concrete platform reading “Freedom Is Not Free.”

Click here to read or download a copy of “The Service Eternal.”

WWII Bunker a hidden relic in Solana Beach

In the 1940s, a military dugout built into a coastal hillside helped target enemy ships in Pacific

By Alex Miller, as published by The Coast News, April 26, 2024

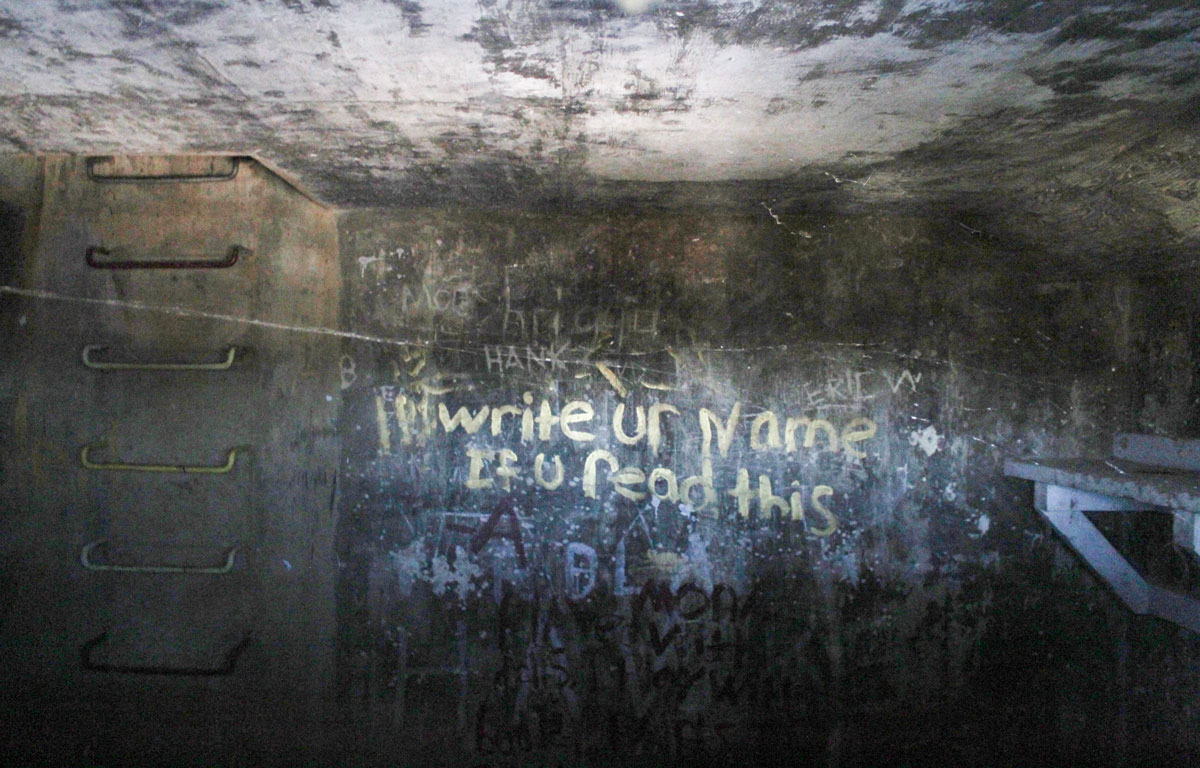

SOLANA BEACH — As the waves crash against the rugged sandstone cliffs of Solana Beach, an unassuming concrete bunker quietly stands testament to a pivotal chapter in American history — a hidden relic built in the early 1940s waiting to unveil its secrets.

Solana Beach Civic and Historical Society historian Richard Moore, a retired nuclear physicist and Army veteran, has helped The Coast News uncover this mystery structure near a private driveway off Marview Lane, just west of Glencrest Drive.

So, what is it, and what was its purpose?

First of all, Moore says it’s not technically a bunker. The reinforced concrete dugout was one of many base-end stations and fire control structures used during World War II to identify enemy ships on the horizon and provide precise coordinates to gun batteries at Fort Rosecrans to the south.

During this time, enemy ships along the California coastline were a real threat. In late February 1942, a Japanese submarine surfaced and shelled the Ellwood oil refinery off the coast of Santa Barbara, destroying a derrick and pumphouse.

Although the attack, known as the Bombardment of Ellwood, caused minimal damage, it invoked “considerable panic” among Americans that the Japanese would continue to attack the West Coast.

In response, the Army Corps of Engineers constructed the “Santa Fe” base-end station, and the engineer’s plans and blueprints are located in the Records of the Adjutant General’s Office in the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

According to the documents, the Santa Fe station is 8 feet tall and 12 feet wide, with only 3 feet above the ground and visible from approximately 75 yards away. The station had no heating, lighting, running water or bathroom but was equipped with a small commercial auxiliary generator generating 125 volts. A separate concrete structure nearby contained a backup generator.

Moore said the fire control structures were solely for observing and reporting target information via telephone to a plotting room for gun batteries at Fort Rosecrans.

“The Solana Beach bunker never had artillery,” Moore said. “Most people mistakenly assume it did, but that’s not the case.”

Moore said fire control structures came in varying sizes, including a two-compartment unit, and one was even built into a fake water tower. The Santa Fe station is similar in appearance to other coastal defenses along the Point Loma Peninsula, namely Battery Ashburn at Fort Rosecrans near the entrance of Cabrillo National Monument Park.

In addition to the Santa Fe, the military’s northernmost fire control structure in Solana Beach, the Army Corps of Engineers built 12 additional units along the San Diego County coastline, stretching as far south as the U.S.-Mexico border. These defenses formed the Coast Artillery Corps, headquartered at Camp Callan on Torrey Pines Mesa, now Torrey Pines Golf Course:

- Site 1: Solana Beach (fire control structure)

- Site 2: Soledad Mountain (fire control structure)

- Site 3: La Jolla Hermosa (fire control structure)

- Site 4: Theosophical/Sunset (fire control structure)

- Site 5: North Fort Rosecrans (fire control structure)

- Site 6: West Fort Rosecrans (gun battery Ashburn)

- Site 7: Cabrillo-Fort Rosecrans (fire control structure and gun battery)

- Site 8: Point Loma (fire control structure)

- Site 9: East Fort Rosecrans (searchlights)

- Site 10: North Island/Coronado (patrol)

- Site 11: Coronado Beach/Silver Strand (fire control structure)

- Site 12: Fort Emory (fire control structure)

- Site 13: Mexican Border (fire control structure).

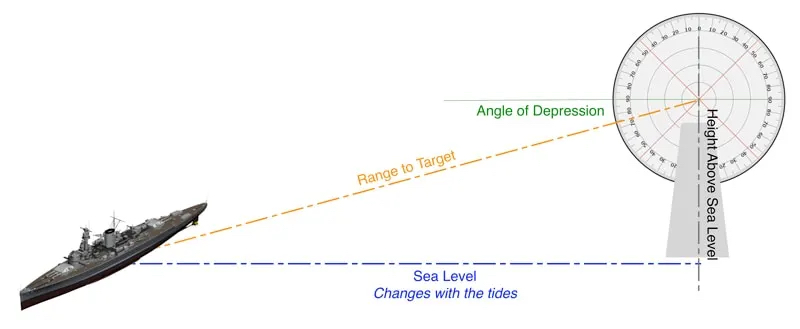

Before radar became available, fire control structures were strategically crucial for coastal defense. “Fire control” is defined as “technical supervision of artillery or naval gunfire on a target” or “controlling” artillery “fire” by relaying detailed target range and elevation data to nearby gun batteries.

Fire control operators used sophisticated observation tools to determine a seafaring enemy vessel’s precise distance and direction, helping ensure coastal artillery rounds hit their intended targets.

One of these tools was a depression position finder, which consisted of a sizeable telescopic lens that calculated the range or distance to a target using a triangle and trigonometry. The position finder even accounts for the Earth’s curve and how light bends. For stability, the depression position finder was mounted atop a large octagonal concrete column inside the station.

One of these tools was a depression position finder, which consisted of a sizeable telescopic lens that calculated the range or distance to a target using a triangle and trigonometry. The position finder even accounts for the Earth’s curve and how light bends. For stability, the depression position finder was mounted atop a large octagonal concrete column inside the station.

One side of the triangle is how high the instrument is above sea level (which changes with the tides and must be adjusted frequently), one angle is always 90 degrees (angle of depression), and the other is how much the instrument points downward (range to target). Once these angles are determined, the observers will know the distance to a ship up to 12,000 yards away.

The other tool was the azimuth scope, a mounted telescope used to determine an enemy ship’s position and track its movements. Further augmenting the fire control operators’ target-finding tools were six searchlights on bluffs above the beaches in Cardiff, Solana Beach, Del Mar’s Dog Beach and near Scripps Pier.

The military triangulated targets from several sources, including other fire control sites, and sightings were reported via telephone from the Santa Fe to Fort Rosecrans Battery Ashburn, one of many coastal defense batteries in California. Battery Ashburn was equipped with heavy artillery — 16-inch guns mounted on large turrets — capable of engaging enemy ships at long ranges.

During the same period, a popular local legend states that an artillery battery was located at Fletchers Cove, with a rectangular cement building serving as ammunition storage. In 1990, the North County Blade-Citizen newspaper erroneously reported this legend, further cementing the tale into local history.

However, Moore said that was just a myth. After the news article was published, retired U.S. Navy Commander Alvin H. Grobmeier wrote a letter to the publisher thoroughly debunking the newspaper’s report.

In his letter, Grobmeier also confirms that the searchlights and station at Site 1 in Solana Beach comprised the Santa Fe fire control structure.

The Santa Fe station is one of the few remaining WWII-era military structures in North County. In the decades following the war, many fire control structures were either lost to time or destroyed by homeowners. The number of structures still in existence is unknown.

Today, Santa Fe sits along a private road in a quiet Solana Beach neighborhood overlooking the ocean, a silent witness to the city’s historical events. The Solana Beach Civic and Historical Society plans to help share the structure’s story and significance with the community for future generations.

Source: The Coast News, April 26, 2024.

Managing Editor Jordan P. Ingram contributed to this report.

Boo-Boo had been looking forward to the Historical Society’s Halloween party all month. He had never been to one before, and was excited to dress up in his best white sheet.

Boo-Boo had been looking forward to the Historical Society’s Halloween party all month. He had never been to one before, and was excited to dress up in his best white sheet. Jackie o’Lantern was feeling excited as she made her way to the community center by the sea. It was the earliest Halloween party of the season, and Jackie loved nothing more than dressing up and celebrating with her friends.

Jackie o’Lantern was feeling excited as she made her way to the community center by the sea. It was the earliest Halloween party of the season, and Jackie loved nothing more than dressing up and celebrating with her friends. The Jinx attended the earliest Halloween party of the season, at a community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon and the days might finally start to get chilly. The Jinx was excited to attend his first Halloween party, but he was also nervous. What would he wear? He had no idea what costumes humans wore. He decided to go as himself and flew to the party in a cloud of dark smoke.

The Jinx attended the earliest Halloween party of the season, at a community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon and the days might finally start to get chilly. The Jinx was excited to attend his first Halloween party, but he was also nervous. What would he wear? He had no idea what costumes humans wore. He decided to go as himself and flew to the party in a cloud of dark smoke. Obscuro was getting excited for the upcoming Halloween party. It would be his first one of the season, and he was looking forward to dressing up in his favorite costume. He had white latex skin that made his face look like a mask, so he always stuck out in a crowd. But that was exactly why he loved going to Halloween parties- he loved the opportunity to show off his unique look.

Obscuro was getting excited for the upcoming Halloween party. It would be his first one of the season, and he was looking forward to dressing up in his favorite costume. He had white latex skin that made his face look like a mask, so he always stuck out in a crowd. But that was exactly why he loved going to Halloween parties- he loved the opportunity to show off his unique look. Lucius Morte had never been to a Halloween party before. He had always been too busy tormenting the damned in the 4th level of hell to bother with earthly celebrations. But this year, he was feeling particularly restless and decided to venture out into the world of mortals. He found a community center by the sea that was hosting a Halloween party and decided to attend.

Lucius Morte had never been to a Halloween party before. He had always been too busy tormenting the damned in the 4th level of hell to bother with earthly celebrations. But this year, he was feeling particularly restless and decided to venture out into the world of mortals. He found a community center by the sea that was hosting a Halloween party and decided to attend. Vespera was so excited to go to the Halloween party. It was at a community center by the sea, and it would be her first party in a long time! She had been practicing her mime and charade skills for weeks, and she was determined to show everyone how good she was.

Vespera was so excited to go to the Halloween party. It was at a community center by the sea, and it would be her first party in a long time! She had been practicing her mime and charade skills for weeks, and she was determined to show everyone how good she was. Gourdy Bane was very excited to attend the earliest Halloween party of the season. It was being held at a community center by the sea, and he loved the sound of waves crashing against the shore. When he arrived, he saw that the party was already in full swing. There were pumpkins everywhere, and people were dressed in costumes. Gourdy Bane saw a couple of gourds wearing pirate costumes, and he couldn’t help but laugh. He loved Halloween parties, and he was having a great time dancing to the music and eating candy.

Gourdy Bane was very excited to attend the earliest Halloween party of the season. It was being held at a community center by the sea, and he loved the sound of waves crashing against the shore. When he arrived, he saw that the party was already in full swing. There were pumpkins everywhere, and people were dressed in costumes. Gourdy Bane saw a couple of gourds wearing pirate costumes, and he couldn’t help but laugh. He loved Halloween parties, and he was having a great time dancing to the music and eating candy. Morrigana was very excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and the days were finally starting to get chilly. Morrigana had been working on her Halloween outfit all year long, and she was looking forward to showing it off.

Morrigana was very excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and the days were finally starting to get chilly. Morrigana had been working on her Halloween outfit all year long, and she was looking forward to showing it off. William Wisp had been looking forward to the community center’s Halloween party all month long. It was going to be two days before the full moon, and he loved the smell of fall in the air (cinnamon and pumpkin spice). His Halloween costume was all ready to go, and he was excited to show it off to all of his friends. This year, he was dressed as a pumpkin. His little orange boots matched his little pumpkin body perfectly.

William Wisp had been looking forward to the community center’s Halloween party all month long. It was going to be two days before the full moon, and he loved the smell of fall in the air (cinnamon and pumpkin spice). His Halloween costume was all ready to go, and he was excited to show it off to all of his friends. This year, he was dressed as a pumpkin. His little orange boots matched his little pumpkin body perfectly. Mr. Creepers was all dressed up and ready to go to the community center by the sea for the earliest Halloween party of the season. It had been a long time since he’d been out and about, but he was feeling young at heart and ready to have some fun. He loved the black 1940s coat that he had found at a thrift store and felt confident that he would be the most stylish person at the party.

Mr. Creepers was all dressed up and ready to go to the community center by the sea for the earliest Halloween party of the season. It had been a long time since he’d been out and about, but he was feeling young at heart and ready to have some fun. He loved the black 1940s coat that he had found at a thrift store and felt confident that he would be the most stylish person at the party. The Frankster had always loved Halloween. He loved the costumes, the candy, and most of all, the parties. This year, he was especially excited for the party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and he could feel a tiny bit of a cool autumn breeze in the air.

The Frankster had always loved Halloween. He loved the costumes, the candy, and most of all, the parties. This year, he was especially excited for the party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and he could feel a tiny bit of a cool autumn breeze in the air. Wooblydook was really excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. He had never been to one before, and he was looking forward to kale pulling and making neep lanterns. The party was two days before the full moon, and Wooblydook was hoping it would start to get chilly soon. He loved being out in the cold and feeling his bat-like ears flap in the wind.

Wooblydook was really excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. He had never been to one before, and he was looking forward to kale pulling and making neep lanterns. The party was two days before the full moon, and Wooblydook was hoping it would start to get chilly soon. He loved being out in the cold and feeling his bat-like ears flap in the wind. As the sun began to set, the community center by the sea came to life. Lights flickered on, announcing that the earliest Halloween party of the season was about to start. A golden sun slowly rose in the sky, growing brighter and brighter as it got closer to the horizon. As it reached its peak, people whispered: this sun only came out at night. It was the Midnight Sun.

As the sun began to set, the community center by the sea came to life. Lights flickered on, announcing that the earliest Halloween party of the season was about to start. A golden sun slowly rose in the sky, growing brighter and brighter as it got closer to the horizon. As it reached its peak, people whispered: this sun only came out at night. It was the Midnight Sun.