Welcome to Our Heritage Museum!

The museum is open monthly on 1st and 3rd Saturdays (1 to 4 pm), by appointment, and during major events in La Colonia Park or at the Community Center. To schedule a visit, please email solanabeachhistoricalsociety@gmail.com.

The Solana Beach Heritage Museum is located at 715 Valley Avenue, Solana Beach, California, in La Colonia Park. Built in 1887, the Museum is the first home built in the community. For 101 years it sat on Pepper Tree Lane, later renamed Del Mar Downs Road, overlooking the San Dieguito estuary and today’s Fairgrounds and Race Track. Threatened with demolition, it was moved to La Colonia Park where it is owned by the City of Solana Beach and operated as a museum by the Solana Beach Civic and Historical Society.

In a visit to the Museum, you will discover the key to sleepy Lockwood Mesa’s transformation into bustling Solana Beach.

In the early 1920’s the neighboring communities had running water, electricity and gas, and were experiencing significant growth. However, Lockwood Mesa did not have these utilities and had only three homes with eight hardy souls. Their rugged lifestyle is depicted in a 1900 kitchen and parlor featuring a wood stove, ice box, kerosene lamps, hand water pump, manual clothes washer and wringer, treadle sewing machine, hand vacuum cleaner and wind-up phonographs.

In 1923 running water arrived from Lake Hodges and predictably the community, now known as Solana Beach, began a period of rapid growth. The more comfortable lifestyle of the new residents is shown in the 1930’s kitchen and living room containing a sink with faucets, refrigerator, gas stove, washing machine with spin dryer, wall phones, Hoover vacuum, electrified sewing machine, cabinet radio and player piano.

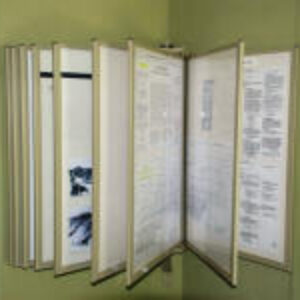

A time-line photo exhibit traces the arrival of Indians, Spanish explorers, Mexican Silver Dons, American farmers and Mexican ranch hands. Early pictures of the development of the community of Solana Beach also are featured.

In 2023, the Society installed a new-fangeled “smart” television so we can share this slideshow about our community’s history, as well.

Members of the Solana Beach Civic and Historical Society annually don period attire and present a Living History Program for area third-grade students. Thank you notes from visiting school-children often highlight their new insights into life in the Stevens home: “I learned that the Stevens never needed a gym because they did their chores as their exercise.”

The Museum also hosts scout troops and groups from retirement centers and senior citizens clubs.

Boo-Boo had been looking forward to the Historical Society’s Halloween party all month. He had never been to one before, and was excited to dress up in his best white sheet.

Boo-Boo had been looking forward to the Historical Society’s Halloween party all month. He had never been to one before, and was excited to dress up in his best white sheet. Jackie o’Lantern was feeling excited as she made her way to the community center by the sea. It was the earliest Halloween party of the season, and Jackie loved nothing more than dressing up and celebrating with her friends.

Jackie o’Lantern was feeling excited as she made her way to the community center by the sea. It was the earliest Halloween party of the season, and Jackie loved nothing more than dressing up and celebrating with her friends. The Jinx attended the earliest Halloween party of the season, at a community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon and the days might finally start to get chilly. The Jinx was excited to attend his first Halloween party, but he was also nervous. What would he wear? He had no idea what costumes humans wore. He decided to go as himself and flew to the party in a cloud of dark smoke.

The Jinx attended the earliest Halloween party of the season, at a community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon and the days might finally start to get chilly. The Jinx was excited to attend his first Halloween party, but he was also nervous. What would he wear? He had no idea what costumes humans wore. He decided to go as himself and flew to the party in a cloud of dark smoke. Obscuro was getting excited for the upcoming Halloween party. It would be his first one of the season, and he was looking forward to dressing up in his favorite costume. He had white latex skin that made his face look like a mask, so he always stuck out in a crowd. But that was exactly why he loved going to Halloween parties- he loved the opportunity to show off his unique look.

Obscuro was getting excited for the upcoming Halloween party. It would be his first one of the season, and he was looking forward to dressing up in his favorite costume. He had white latex skin that made his face look like a mask, so he always stuck out in a crowd. But that was exactly why he loved going to Halloween parties- he loved the opportunity to show off his unique look. Lucius Morte had never been to a Halloween party before. He had always been too busy tormenting the damned in the 4th level of hell to bother with earthly celebrations. But this year, he was feeling particularly restless and decided to venture out into the world of mortals. He found a community center by the sea that was hosting a Halloween party and decided to attend.

Lucius Morte had never been to a Halloween party before. He had always been too busy tormenting the damned in the 4th level of hell to bother with earthly celebrations. But this year, he was feeling particularly restless and decided to venture out into the world of mortals. He found a community center by the sea that was hosting a Halloween party and decided to attend. Vespera was so excited to go to the Halloween party. It was at a community center by the sea, and it would be her first party in a long time! She had been practicing her mime and charade skills for weeks, and she was determined to show everyone how good she was.

Vespera was so excited to go to the Halloween party. It was at a community center by the sea, and it would be her first party in a long time! She had been practicing her mime and charade skills for weeks, and she was determined to show everyone how good she was. Gourdy Bane was very excited to attend the earliest Halloween party of the season. It was being held at a community center by the sea, and he loved the sound of waves crashing against the shore. When he arrived, he saw that the party was already in full swing. There were pumpkins everywhere, and people were dressed in costumes. Gourdy Bane saw a couple of gourds wearing pirate costumes, and he couldn’t help but laugh. He loved Halloween parties, and he was having a great time dancing to the music and eating candy.

Gourdy Bane was very excited to attend the earliest Halloween party of the season. It was being held at a community center by the sea, and he loved the sound of waves crashing against the shore. When he arrived, he saw that the party was already in full swing. There were pumpkins everywhere, and people were dressed in costumes. Gourdy Bane saw a couple of gourds wearing pirate costumes, and he couldn’t help but laugh. He loved Halloween parties, and he was having a great time dancing to the music and eating candy. Morrigana was very excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and the days were finally starting to get chilly. Morrigana had been working on her Halloween outfit all year long, and she was looking forward to showing it off.

Morrigana was very excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and the days were finally starting to get chilly. Morrigana had been working on her Halloween outfit all year long, and she was looking forward to showing it off. William Wisp had been looking forward to the community center’s Halloween party all month long. It was going to be two days before the full moon, and he loved the smell of fall in the air (cinnamon and pumpkin spice). His Halloween costume was all ready to go, and he was excited to show it off to all of his friends. This year, he was dressed as a pumpkin. His little orange boots matched his little pumpkin body perfectly.

William Wisp had been looking forward to the community center’s Halloween party all month long. It was going to be two days before the full moon, and he loved the smell of fall in the air (cinnamon and pumpkin spice). His Halloween costume was all ready to go, and he was excited to show it off to all of his friends. This year, he was dressed as a pumpkin. His little orange boots matched his little pumpkin body perfectly. Mr. Creepers was all dressed up and ready to go to the community center by the sea for the earliest Halloween party of the season. It had been a long time since he’d been out and about, but he was feeling young at heart and ready to have some fun. He loved the black 1940s coat that he had found at a thrift store and felt confident that he would be the most stylish person at the party.

Mr. Creepers was all dressed up and ready to go to the community center by the sea for the earliest Halloween party of the season. It had been a long time since he’d been out and about, but he was feeling young at heart and ready to have some fun. He loved the black 1940s coat that he had found at a thrift store and felt confident that he would be the most stylish person at the party. The Frankster had always loved Halloween. He loved the costumes, the candy, and most of all, the parties. This year, he was especially excited for the party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and he could feel a tiny bit of a cool autumn breeze in the air.

The Frankster had always loved Halloween. He loved the costumes, the candy, and most of all, the parties. This year, he was especially excited for the party at the community center by the sea. It was two days before the full moon, and he could feel a tiny bit of a cool autumn breeze in the air. Wooblydook was really excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. He had never been to one before, and he was looking forward to kale pulling and making neep lanterns. The party was two days before the full moon, and Wooblydook was hoping it would start to get chilly soon. He loved being out in the cold and feeling his bat-like ears flap in the wind.

Wooblydook was really excited to attend the Halloween party at the community center by the sea. He had never been to one before, and he was looking forward to kale pulling and making neep lanterns. The party was two days before the full moon, and Wooblydook was hoping it would start to get chilly soon. He loved being out in the cold and feeling his bat-like ears flap in the wind. As the sun began to set, the community center by the sea came to life. Lights flickered on, announcing that the earliest Halloween party of the season was about to start. A golden sun slowly rose in the sky, growing brighter and brighter as it got closer to the horizon. As it reached its peak, people whispered: this sun only came out at night. It was the Midnight Sun.

As the sun began to set, the community center by the sea came to life. Lights flickered on, announcing that the earliest Halloween party of the season was about to start. A golden sun slowly rose in the sky, growing brighter and brighter as it got closer to the horizon. As it reached its peak, people whispered: this sun only came out at night. It was the Midnight Sun.